Jon-Adrian (JJ) Velazquez has recently sued New York City and its police for $100 million stemming from his wrongful murder conviction.

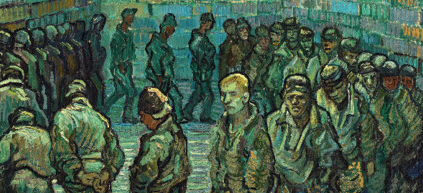

Valazquez is best known for his role in the Oscar nominated film Sing Sing depicting how he and other prisoners had formed a theatre group in the maximum security prison where he was imprisoned for 23 years.

Velazquez’s case, including his claim for compensation, demonstrates American exceptionalism when it comes to wrongful convictions, a phenomenon I document in my new book Justice for Some available in open access from Cambridge Core.

In Justice for Some, I argue that the United States, unlike other democracies, insists on proof of factual innocence to remedy wrongful convictions. This strict rationing of justice is related to its continued use of mass imprisonment. It has also produced world leading levels of compensation for the wrongfully convicted.

The concept of proven factual innocence is powerful in part because it is populist and more easily understood than the concepts of miscarriages of justice, the safety of convictions or judicial error used in many other countries.

The American National Registry of Exonerations has recorded over 3,700 exonerations since the advent of DNA testing in 1989. These cases have resulted in over 35,000 lost years in prison. They have also resulted in over $4.5 billion being paid in compensation even though less than half of exonerees receive any compensation at all. https://exonerationregistry.org

My book also makes use of a United Kingdom registry that records just under 500 remedied wrongful convictions since the 1970s.

Registries for both continental Europe and Canada record less than 135 remedied wrongful convictions in each registry.

In short, the United States produces many more wrongful convictions than other democracies. At the same time, it also remedies compensates them at a world leading rate.

The country closest to the United States is the Peoples Republic of China, another mass imprisonment society. Like the US, China insists on proof of factual innocence, often as after multiple court hearings. China has also started compensating those who can prove their factual innocence more generously. At the same time, there are dangers that in both countries generous compensation for the few may help legitimate unjust legal systems for the many.

Although strongest in the United States and China, populist requirements for proven innocence are spreading. Since 2014, they are required to receive compensation for miscarriages of justice in England and Wales. This regressive change had resulted in drastic declines in amounts paid to compensation and denial of compensation to those such as Victor Nealon who were excluded by DNA.

American reformers have proposed that a right to claim innocence should be added to international law but this may have regressive implications in many other parts of the world.

To be sure those who can prove their innocence should receive justice. But they are not the only ones who should receive justice.

Valazquez’s case illustrates the power of proven factual innocence and its populist appeal. He received remedies first from the press and then the elected executive before American courts finally overturned his wrongful murder conviction.

Velazquez was freed from prison not by American courts but by a grant of clemency from then New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in 2021. In 2022, President Joe Biden apologized to Valazquez for his wrongful conviction. These elected politicians were influenced not only by Valazquez’s good works but by media reporting and a private lab’s testing in 2020 that produced a DNA exclusion from a betting slip that the perpetrator had handled.

In the years since, and as detailed in my book, executive clemency has become politically polarized in the United States. There is a danger that political polarization may produce a post-truth world where even factual innocence may be less valued.

The fact that politicians who hoped for re-election were ahead of American courts with respect to exonerating Valazquez reveals much about the decline of the rule of law in the United States.

After his 2000 conviction, Valazquez’s appeal was denied as is typical in American exoneration cases. American appeal courts focus on legal error and have stricter standards for considering new evidence than courts in many other countries.

In 2006, Valazquez representing himself filed for federal habeas corpus. American legalism allows more opportunity for the convicted to claim relief, first in state and then in federal courts.

This relief was denied with the Federal Court judge stressing that Congress in its Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 had restricted habeas corpus. Valazquez had not proven his innocence as required by clear and convincing evidence. The court stressed that prior courts had upheld convictions in other cases, like Valazquez’s case, where eyewitnesses gave inconsistent details about their testimony.

Mistaken eyewitness identification is a leading cause of wrongful convictions.

The inconsistencies in Valazquez’s case were striking. Some witnesses had initially identified the perpetrator as a Black man with long braided hair whereas Valazquez is Hispanic and had very short hair. Some said the perpetrator used his right hand to shoot the victim whereas Valazquez is left-handed. The court deferred to the jury which had rejected Valazquez’s alibi defence even though it was supported by phone records and the testimony of his mother and girlfriend.

Valazquez kept asserting his innocence but in 2016 a five judge New York appeals court unanimously rejected his claim of factual innocence. The fact that two of four eyewitness who identified him as the perpetrator at trial had recanted and another man had confessed to being the shooter was not enough to even justify either a full hearing on Valazquez’s motion or a new trial.

The Court again insisted on clear and convincing evidence of innocence standard which explained required that innocence be “highly probable”. This is a much less generous standard than applied by the English Court of Appeal and many others in the Commonwealth which focus on whether a guilty verdict is safe or reasonable or constitutes a miscarriage of justice.

It was not until 2024 and with the consent of then Manhattan District Attorney Melvin Bragg that a court overturned Valazquez’s wrongful murder conviction. Without the magic of DNA evidence, he may never have been exonerated despite the many weaknesses in the evidence used to convict him. This is a sign of a mass imprisonment society that assigns too much weight to the finality of convictions.

Valazquez told reporters that his exoneration was a “bittersweet unveiling of a tragedy” He stressed “People really don’t get what it’s like to be in prison” where all prisoners receive inadequate medical care and many die after being released. He stated “It’s important to keep hope alive for that many people, because we have hundreds of thousands of people potentially that are innocent, languishing in prisons right now… it’s really about the movement. It’s about the people, it’s about the injustices, and it’s about how we can leverage our voices and come together to really try to demand change that’s necessary.” “Criminal Justice Advocate Jon-Adrian Valazquez cleared of wrongful homicide conviction” New York Amsterdam News Oct 3, 2024.

Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck, the founders of the American Innocence Project, argued 25 years ago that DNA exonerations were largely a matter of luck and would eventually dry up as police used DNA testing in the small minority of crimes involving biological evidence.

Scheck and Neufeld deserve a Nobel Prize and other honours for their successful work in a hostile and punitive environment. Nevertheless, they may have been overly optimistic about the competence of American police and prosecutors in their 2000 book. DNA exonerations, like Valazquez’s continue to this day.

But DNA has been a double edged sword. Although it provides powerful evidence of innocence, it has helped raise the standard for remedying wrongful convictions. It only provides justice for some.

The United States has embraced high and populist standards of proven innocence. They provide justice for some but they threaten to eclipse more generous standards of remedying wrongful convictions used in other democracies that provide justice for more.

Kent Roach is a Professor of Law at the University of Toronto and Co-Founder of the Canadian Registry of Wrongful Convictions

Latest Comments

Have your say!