With these words Rudyard Kipling explained the Indian revolt against the British in 1857. Nearly a century after Kipling’s novel was published, Edward Said would draw attention to the necessary tendentiousness of Kipling’s depiction. Naturally the British would insist on an imperial understanding of the rebellion as a product of Indian madness (and how better to do this than through the lips of a loyal Indian veteran of 1857?). Just as naturally, Indian nationalists by the turn of the twentieth century would insist upon an understanding of the revolt as a patriotic, and perfectly reasonable, Indian reaction to foreign domination. Hence V. D. Savarkar’s 1908-9 account of 1857 as The First War of Indian Independence.

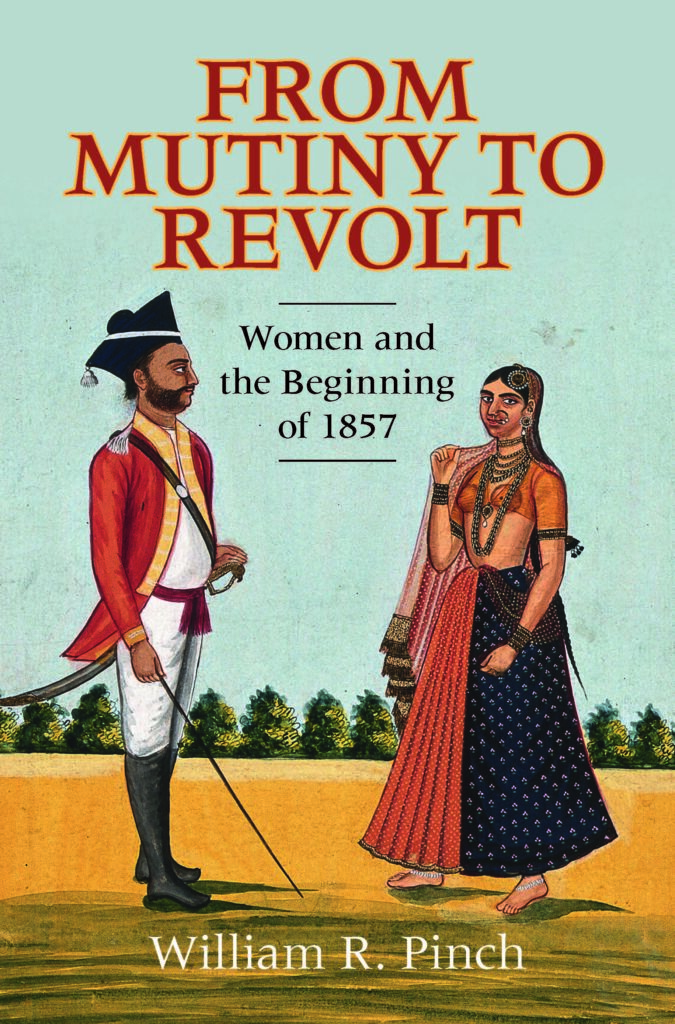

As perceptive as Said’s observations were, they raise a host of questions, not least of which is, why did the Company Army revolt in 1857? It is this question that opens my microhistory, From Mutiny to Revolt: Women and the Beginning of 1857.

The answer that historians invariably give to this question begins with a “greased cartridge.” In short, according to the standard narrative, 1857 was the inexorable outcome of a refusal by entire regiments to perform a “firing drill” in which soldiers practiced the synchronized loading, firing, and reloading of their weapons. This refusal constituted, in military parlance, a mutiny. The reason for these regimental refusals, or mutinies, in the early months of 1857 was the suspicious nature of a new greased cartridge—or more specifically, the grease for the cartridge—that was associated with the introduction of a new weapon, the Pattern 53 Enfield rifle (or, technically “rifled musket”). As rumors spread about the use of cow and pig fat in the manufacture of these new cartridges, anxieties among the “native” soldiery extended to the cartridges designed for their existing weapons as well, the old “Brown Bess” long in use in the Company Army. So closely associated in the British mind was the refusal to perform the firing drill with the later explosion of violence in 1857 that the British quickly came to refer to the explosion of violence in 1857 with the term “Mutiny.” This discursive association became so ingrained in British imperial historiography that one could write an entire book under the title Mutiny as Metonymy.

But notice the historiographical sleight of hand: 1857, a violent Indian uprising—whether we call it a War of Indepence or a Sepoy Mutiny—was due to a mass refusal to load and fire a weapon. As such, in Gandhian terms, we might regard it as an inherently non-violent mutiny, a military act of “non-cooperation.” But nonviolent non-cooperation is the antithesis of a violent uprising. Thus the more I pondered these facts, the more I realized that the question posed above remained unanswered.

Let us therefore rephrase the question: What caused the nonviolent mutinies of 1857 to explode into the violent Mutiny (so-called) of 1857?

For an answer I look to Meerut on May 10th 1857. This is where and when Indian soldiers in the Company Army first rose up en masse to attack and kill their British officers. Two weeks earlier, in late April, eighty-five men of the Bengal 3rd Light Cavalry, stationed at Meerut, had refused to perform the firing drill—apprehensive as they were about the cartridges. They were court martialed soon thereafter and placed in confinement. On 9 May, they were ceremonially stripped of their uniforms, placed in irons, and marched off to prison, like many men before them that year in cantonments across north India. But for some reason events unfolded differently in Meerut. Late in the afternoon on the following day, the men of the 3rd Light Cavalry, joined by the 20th Native Infantry and most of the 11th Native Infantry, suddenly began killing their British officers.

What was it about Meerut in the intervening hours on the 9th and 10th of May 1857 that prompted the fateful decision by the men of the 3rd Light Cavalry to spill the blood of their British officers? The official history written by John Kaye in the 1860s offers the following explanation:

The 3rd Cavalry were naturally the most excited of all. Eighty-five of their fellow soldiers were groaning in prison. Sorrow, shame, and indignation were strong within them for their comrades’ sake, and terror for their own. They had been taunted by the courtesans of the Bazaar, who asked if they were men to suffer their comrades to wear such anklets of iron;* and they believed that what they had seen on the day before was but a foreshadowing of a greater cruelty to come.

It was this taunting, Kaye maintained, that moved the men to attack their officers and free their comrades in prison.

But who were these “courtesans of the Bazaar”? As one follows the evidentiary bread crumbs, more questions emerge. At the bottom of the page in question, Kaye cited the “excellent authority” of one J. Cracroft Wilson in his “interesting Muradabad report.” Wilson’s 1858 report did indeed describe the “frail ones” (a popular euphemism for prostitutes) of the Meerut bazaar taunting the men of the 3rd Light Cavalry and calling into question their masculinity. Wilson further held that the men could not withstand the emotional force of these women’s taunts. In short, the women drove them mad.

There is much more to this story of exploding masculinity, including corroborating sources beyond Wilson’s account. I recount this history and much else besides in From Mutiny to Revolt. Almost as “interesting” as Wilson’s report, however, is how the story of the “bazaar women” has evolved over the years, becoming by the late nineteenth century a staple of imperial “Mutiny” literature and historiography, and later nationalist and post-nationalist narrative history.

The further down one drills, the more varied the evidence becomes—including variations on the theme of who, precisely, the bazaar women of Meerut were. The story of the women of Meerut thus opens a window, I argue, onto the social and emotional world of the Company Army in the mid nineteenth century.

Latest Comments

Have your say!