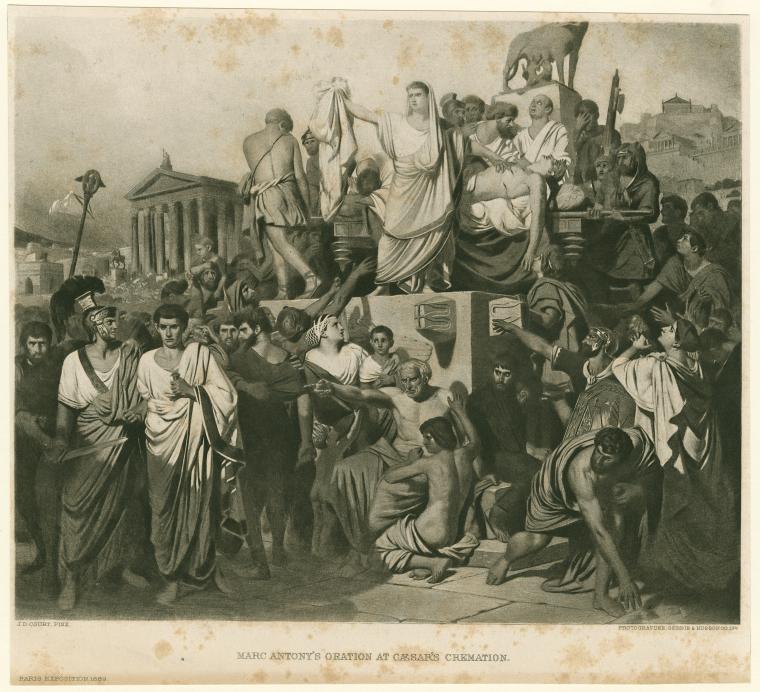

In Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Marc Antony famously begins his funeral oration by exclaiming, “Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears.” This is an elegant way of asking for attention. At the same time, it engages with important ideas about ears and audition in the early modern period and the degree to which listening might be an intentional act.

Early modern discourses about audition were highly ambivalent. On the one hand, early modern authors talked about hearing as the most impactful of the senses. Sir Francis Bacon, for instance, singles out audition in his Sylva Sylvarum (1626) as the sense with the most effect on our manners. According to Bacon, this is because ‘the Sense of Hearing striketh the Spirits more immediately than the other Senses and more corporeally than Smelling: for the Sight, Taste, and Feeling, have their Organs, not of so present and immediate Access to the Spirites, as the hearing hath’. Richard Braithwaite agrees that audition is in a class by itself, advising in his Essaies Upon the Five Senses (1620) that the ear has ‘a distinct power to sound into the centre of the heart’. Robert Wilkinson expresses a similar notion in A Iewell for the Ear (1625), describing the ear as the ‘doore of the hart’ and explaining that ‘God neuer commeth so neere a mans soule, as when he entreth in by the doore of the eare’.

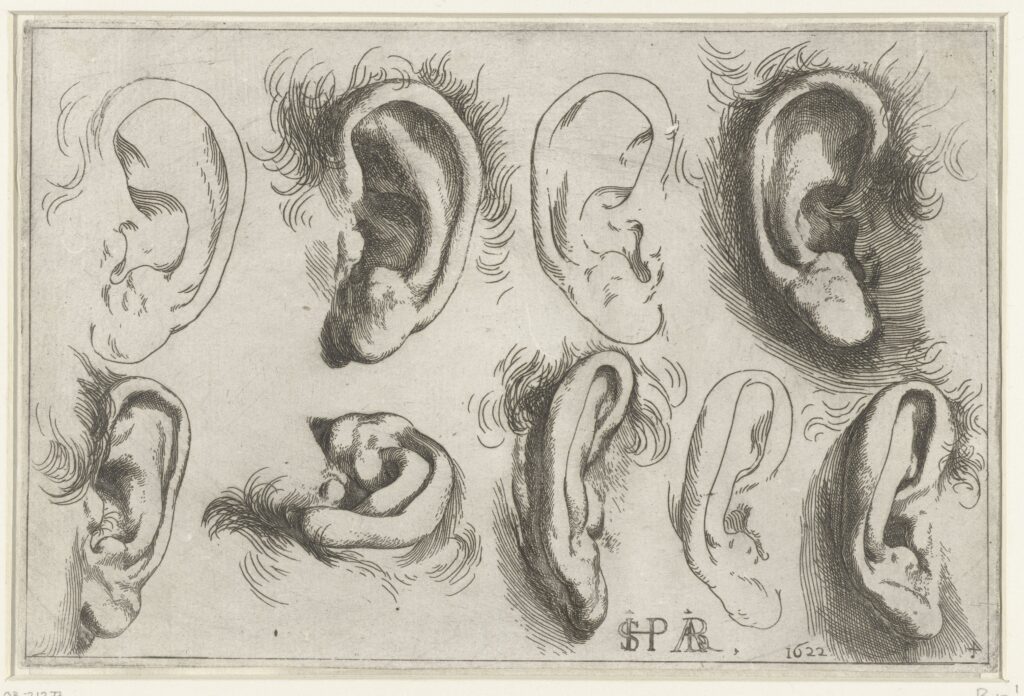

However, early modern authors not only figured the ear as an ‘always open’ orifice but also as an elaborately constructed defensive mechanism. While the auditory canal was said to operate as a funnel that draws in sound, it was also conceptualized as a series of checkpoints and barriers that could prevent sounds from penetrating. In other words, writers like Braithwaite and Wilkinson were divided as to whether listening is voluntary or involuntary, whether it is within or without one’s conscious control.

Robert Wilkinson embraces the idea of auditorial agency when he distinguishes between three types of hearers: those who merely ‘apprehend an outward sound’, those who listen solely ‘to haue their eares tickled’, and those who make an effort to ‘performe attention’ and ‘hearken’. Exhorting his parishioners to be the latter, Wilkinson urges them to ‘moue their eares’ towards those who preach God’s word and ‘meete them in the halfe way with eares’. Similarly, Richard Braithwaite plays up the elective nature of listening when he asserts that we can shut our ears, if not physically like the eye by way of the eyelid, then attentively so by way of ‘free will’ and ‘pure consecrated desire’. Thus, a cautious ear can become ‘barracadoed against the insinuating desires of euery seducing appetite’. According to Braithwaite, ears are neither passive nor inert. To the contrary, audition is ‘one of the actiuest & laborioust faculties’. According to him, ‘A discreet eare seasons the vnderstanding’ and collaborates ‘with iudgement’ to determine ‘whether that which it hath heard, seeme to deserue approbation’.

How does Shakespeare approach the agency of the ear? This is one of the questions I take up in my book, Voice and Ethics in Shakespeare’s Late Plays. One of the things I observe is that Shakespeare’s plays–especially those written in his maturity–regularly foreground the act of listening. These plays are replete with references to the ear. When alluding to ears, though, Shakespeare often adds an adjective. In his works, he asks us to imagine persons with dull ears, healthful ears, grieved ears, willing ears, attent ears, foolish ears, knowing ears, greedy ears, grave ears, quick ears, licentious ears, treacherous ears, diligent ears, open ears, kindest ears, warlike ears, heedful ears, aged ears, ancient ears, ruined ears, sickly ears, pregnant ears, credent ears, patient ears, mad ears, deaf ears, married ears, savage ears, and sad ears. The astonishing range and richness of this inventory attests to Shakespeare’s emphasis on the act of hearing, as well as his sense of it as an ethically charged behavior. What ear we use when listening to others fundamentally shapes our reception, interaction, and relation. One can hear in a variety of ways, some more responsive/responsible than others. In Voice and Ethics, I argue that Shakespeare’s later plays are intent on exploring the moral and ethical weight audition bears. In these works, every voice lays claim to our attention, imploring us to lend our ears.

Voice and Ethics in Shakespeare’s Late Plays by Kent Lehnhof

Latest Comments

Have your say!