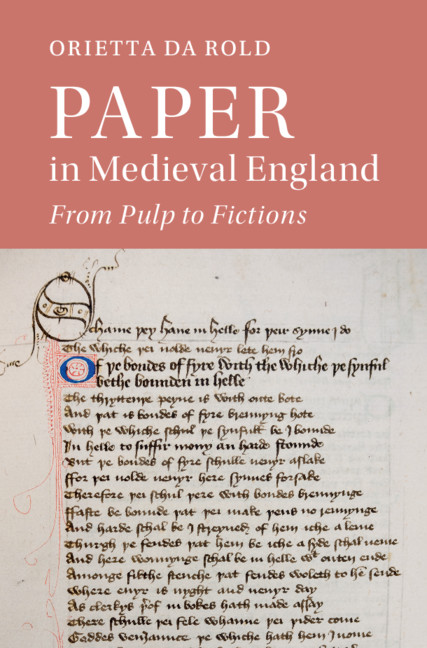

When I started to dream up my book Paper in Medieval England: from Pulp to Fictions, I wanted to find out why medieval people were interested in paper and how paper became a success story in pre-modern times. It was a project of discovery as well as deep frustration. Paper seemed to have quite a reputation in medieval discourses on materiality and book production: a cheap and ephemeral material, used to save on cost of books and constantly in competition with another writing material, parchment, animal skin. Yet the story of medieval paper unfolded in a far richer narrative of technological acceptance and transnational interactions. [1]

Pretty much like in modern time, evidence of paper by the end of the fourteenth century could be found everywhere: in correspondence, medical recipes, household uses, book production, charms. It was used for the quotidian and the extraordinary. It was a tool as well as an idea. Medieval people fully understood the affordances of paper, using them to their own advantage to fulfil continuous and new needs. In this respect, paper was perceived in not a dissimilar way from how modernity understands it. Its chromaticity, porosity, plasticity and tensility were employed in creative ways across culture, society and industry.

Thus the book rewrites the story of paper in medieval England by examining paper in culture and culture in paper. I investigate the journey of paper to England from its earlier arrival in the thirteenth century to its full acceptance in a range of uses from wrapping goods to writing. I discuss the economics of the paper trade and the human interactions that such trade enabled. Paper was brought to England by the international economic relationships that the country enjoyed with other European countries, such as Italy. I consider the affordance of paper across a wide range of appropriations and writing environments. Paper was used by people imaginatively for writing and beyond, it captured the literary imagination of Dante, Chaucer, the Gawain Poet and Dafydd ap Gwilyn.

From its first introduction to the West during the eleventh century, medieval people began to invest in papermaking and by the end of the thirteenth century they transformed a local craft into a transnational success. If paper was created as a writing material, as a useful tool to record the economic growth of medieval Europe and its diplomatic exchanges, it soon became the means through which people communicated knowledge of all kind. By a process of slow and continuous interactions, paper started to be used in epistolary culture, then in book production, and then in medical recipes to dress wounds and whiten teeth. [2]

In book production people use paper creatively in different formats and combining it freely with parchment, often making paper and parchment work together rather than one against each other. We often assume that technologies compete against each other for a place of primacy in society, but rather than revolution paper contributed to the steady increasing demand of large quantities of writing surfaces. This book calls into question perceived knowledge about medieval paper, shedding light on how it was often perceived as a luxury item, a ground-breaking technological advance, which was renowned for possessing desirable properties. It sheds new light in the pre-modern, pre-printing period showing a complex and important cultural history of paper. As I conclude: ‘Why paper? Because of its affordances, not its affordability’.

[1] O. Da Rold, ‘From Pulp to Fiction: our love affair with paper’, University of Cambridge Press released from the Horizon article, 17 March 2016 <http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/features/from-pulp-to-fiction-our-love-affair-with-paper>

[2] O. Da Rold, ‘Paper As Commodity In Medieval Magical And Medical Practices’, Recipes Project, 6 August 2016 <https://recipes.hypotheses.org/8358>

Latest Comments

Have your say!