A Literary Disclosure. Original held by Cambridge University Library.

Nine sheets of paper preserve a life.

I often think, finding fragments in the Press Archive, how precarious is the line between preservation and destruction. Survival depends on so many chances and decisions – like a bullet striking one soldier but missing his comrade. These pages preserve a life because they preserve a story.

He saved lives in war time, shot a man in peace time and wrote a book for the Press to keep himself sane.

‘The youth of today is often ignorant of the very names of the chief battles of the War’[i]. Our refrain in 2014 is the need to remember the unimaginable millions and the unique individuals, but these words were written just seven years after the end of the First World War.

A fear of forgetting prompted the book which would become An Outline History of the Great War. The ‘generation whose parents helped to make the history of those critical years’ deserved a special type of book: one ‘short enough to be read in a single school term’, one without ‘the false glamour which is apt to be shed on war’.

The cover of ‘An Outline History of the Great War‘, held at the Cambridge University Library.

An eminently qualified author was found: distinguished military service, first-hand experience of the war, educated, cultured, a fine writing style. One obstacle: he was an inmate of Broadmoor high-security psychiatric hospital. Convicted of murder: ‘Guilty but Insane’.

At the time, Rutherford’s story was a sensation. He was highly esteemed in the medical profession before 1914 and served with distinction in the Royal Army Medical Corps. On 14 January 1919, he entered 13 Clarendon Road, Holland Park, London and shot Major Miles Seton, a fellow medical officer, with a revolver eight times. Official reports cited shell-shock, a condition first defined in 1915. G.V. Carey (then Education Secretary at the Press) noted, in his ‘Literary Disclosure’[ii], those nine fragile sheets of typescript, that Rutherford believed Seton had ‘alienated him from the love of his wife and children’. Rutherford’s final bullet was intended for himself but used inadvertently on his victim.

He wrote a note to his wife and waited to be arrested.

For two military men, Gordon Vero Carey and Hugh Sumner Scott, incarceration in a hospital for the criminally insane was not an insurmountable problem. Scott, a master at Wellington College, had met Rutherford at a cricket match between Wellington and Broadmoor (the staff and the more reliable patients) and had been struck by Norman Rutherford’s ‘literary taste and by his special interest in, and detailed knowledge of, the events of the Great War’.[iii] Scott was convinced that Rutherford had a gift for writing, and that ‘active employment would help to save his reason’.[iv]

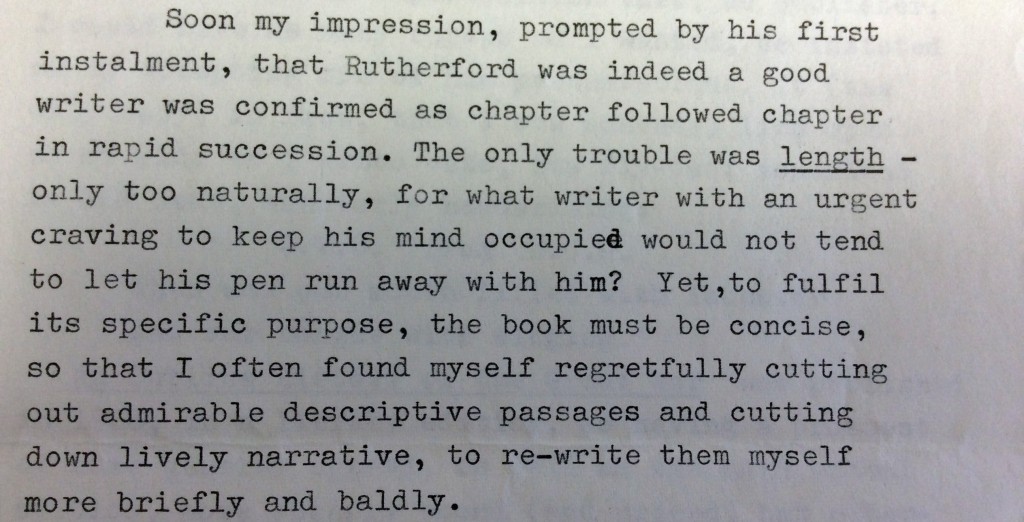

Scott and Carey made frequent visits to Broadmoor, ensured all necessary books were placed at Rutherford’s disposal, and received chapter after chapter in rapid succession. Carey noted, in his ‘Literary Disclosure’, that ‘The only trouble was length – only too naturally, for what writer with an urgent craving to keep his mind occupied would not tend to let his pen run away with him?’.[v] Elegant style, concise chapters, clear maps, half-tone illustrations, this was an admirable Outline.

G. V. Carey comments on Lt-Col Rutherford’s writing style. Original held at Cambridge University Library.

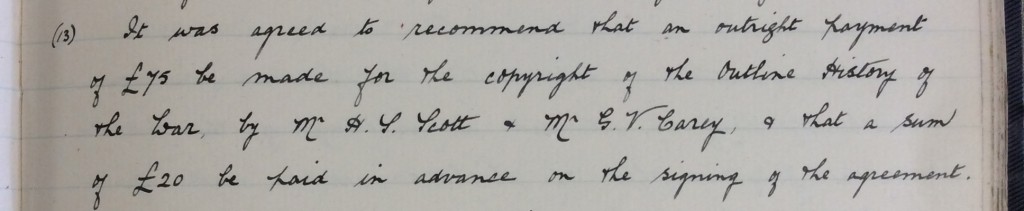

Scott contributed chapters on Palestine, Carey acted as editor, but ‘by and large, the book’s author was Norman Rutherford’.[vi] An ‘outright payment of £75’[vii] was made instead of royalties.

The Home Office forbade the name of a Broadmoor inmate to appear on the cover so, with ‘somewhat guilty consciences,’ Scott and Carey allowed their names to appear as joint authors. Rutherford was mentioned obliquely in the Preface to first edition, in September 1928, as an ‘anonymous friend’ without whom ‘this book could not have been written’.

A year later, in the second edition, the friend was named with military rank and honours: Lieut.-Colonel N.C. Rutherford, D.S.O., late R.A.M.C.

The Business Sub-syndicate Minute Book notes the payment of £75 for ‘An Outline History of the Great War’, but not to Rutherford. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

The writing of this book saved Rutherford’s reason and its publication ensured his freedom.

Within a week, Scott sent a copy of the Outline History to the Home Secretary Sir William Joynson-Hicks, ‘with a covering letter describing fully Rutherford’s part in its production’.[viii] The effect was immediate and Rutherford was released quietly from Broadmoor. On 11 January 1929, Carey reported to the Press Syndicate ‘that Col. N.C. Rutherford was no longer an inmate of Broadmoor; but that he was not anxious for his name to appear in connection with any future edition of An Outline History of the Great War’.[ix]

He was reinstated to the Medical Register but, to protect the reputation of his family, he spent most of his remaining years abroad as a specialist in eye surgery in Canada, Austria and Persia. His granddaughter recalled that ‘he asked to be buried with his tin hat from the trenches‘.

Eloquent prose, clear structure, historical reference and contemporary relevance led the Press to issue the second edition as a Print on Demand book in 2011. Rutherford’s ‘outline’ is present in his words and in the Preface but remains, as was his wish, absent on the title page.

Never let an offhand remark that archives are ‘dry’ or ‘dusty’ go unchallenged.

They contain all human emotion: love, fury, compassion, regret. In these next four years of remembrance, photographs, typescripts, notebooks and diaries serve to draw soldiers’ lives from obscurity to recognition.

G.V. Carey’s recollections preserved for posterity allow us to give belated acknowledgement to Norman Rutherford, Press author.

[i] An Outline History of the Great War by G.V. Carey and H.S. Scott (Cambridge: 1928, 1929 and 2011)

[ii] G.V. Carey ‘A Literary Disclosure’. Undated typescript. [provisional reference UA PRESS 1/5/1/5/20]

[iii] ‘A Literary Disclosure’ p.3

[iv] ‘A Literary Disclosure’ p.3

[v] ‘A Literary Disclosure’ p.4

[vi] ‘A Literary Disclosure’ p.5

[vii] UA Pr.V. 61. Business Subsyndicate Minute Book

[viii] ‘A Literary Disclosure’ p.6

[ix] UA Pr.V.80 Press Syndicate Minute Book

Latest Comments

Have your say!