In the end, it wasn’t enough. Despite closing the substantial lead enjoyed by his rival on the morrow of the first round of the French presidential election, Nicolas Sarkozy was still defeated by François Hollande by over three percentage points (48.47% vs. 51.63%) in the second round run-off. As such, Sarkozy is the first incumbent president to fail in his bid for reelection since 1981 while Hollande becomes the first Socialist to win the presidency since 1988.

A number of factors explain this result. At a broad comparative level, Sarkozy is the eleventh European leader to be turned out of office since the onset of the eurozone sovereign debt crisis that began in the fall of 2009, reflecting the revolt of European electorates against the generalized austerity policies that have been adopted in order to combat it. Yet this is only half the story. Alongside the rejection of his economic policies, Sunday’s result also represented a singular rebuke of Sarkozy’s persona. After a term punctuated by his cultivation of a ‘bling-bling’ lifestyle that ensconced his reputation as the president of the rich—his first act on the night of his election in 2007 was to invite his wealthiest backers to a celebratory dinner at Le Fouquet’s, one of Paris’s most exclusive brasseries—, a series of campaign financing scandals, and an unpredictable, brusque and coarse leadership style diametrically at odds with the regal sense of grandeur once incarnated by Charles de Gaulle, the Fifth Republic’s exemplary founder, and which the French have come to expect in their presidents, a majority of voters simply could not bear another five years of seeing Sarkozy on their TV screens. In this context, what might well have been perceived as a weakness for Hollande, his quiet, deliberate, even boring, style turned out to be strength, a sentiment ably summed up by the daily Libération when it qualified his victory as the triumph of monsieur normal.

So what does this outcome bode, both for Europe and for France? In terms of Europe and the crisis of the eurozone, Hollande’s election—as he himself asserted in his victory speech to his supporters assembled on the Place de la Bastille—has aroused great hopes in other European countries by heralding a turn against the policies of lockstep austerity that have been imposed by Germany in favor of adopting pro-growth reflationary policies, notably through renegotiating the European budgetary pact. However, there are reasons to be circumspect about this prognosis. Politically, Hollande’s navigation of the crisis, which will likely determine whether his term is deemed a success or failure, depends on his ability to constructively work with Germany—and Angela Merkel—in order to resolve it. Notwithstanding the latter’s unconcealed support for Sarkozy during the campaign, it is in both their interests to mend fences quickly and break the current impasse. However, this will be far from easy, as they face contradictory political imperatives and electoral pressures. Whereas Merkel’s domestic political fortunes depend on maintaining the course of austerity, for Hollande the opposite is true—particularly as he has very publicly situated himself at the helm of Europe’s anti-austerity camp. How this circle is to be squared is anybody’s guess, but the answer—or at least the outline of one—is likely to emerge at the May 23rd meeting of EU leaders in which Hollande will be forced to declare himself regarding the Greek bailout. In the interests of European unity, he is likely to reaffirm France’s commitment to enforcing the terms of the latter—and thereby disappoint his voters—but his hand will be considerably weakened if, in exchange, he is unable to secure pro-growth concessions from Germany. (On this score, Merkel remains adamantly opposed to the creation of Eurobonds or to allowing the European Central Bank to lend directly to states in order to alleviate their debts, the two revisions proposed by Hollande to the European budgetary pact). Hollande would go into the June parliamentary elections an already wounded figure, which could reduce the parliamentary majority and constrain the policy autonomy of the incoming Socialist government.

Economically, however, even if he is able to secure such pro-growth concessions from Merkel, these may still not be enough to salvage Europe’s financial situation. Indeed, the contractionary impact of budgetary austerity might stifle the reflationary benefit of these measures, particularly since the impacts of fiscal policy on aggregate demand precede and outweigh those of monetary policy. Thus, the solvency problems of Greece, Spain and Italy would continue with all the risks this would entail for the eurozone economies and preserving the euro. In this delicate context, Hollande’s domestic plans to expand the public sector, raise taxes on the rich, and restore the retirement age of 60 for certain workers, could spook the financial markets and plunge France into a balance of payments of crisis that would irreparably damage its economy. As in the case of previous French statesmen of the left—Herriot, Blum and Mitterrand come to mind)—, Hollande finds himself confronted to le mur d’argent (‘the wall of money’); the success of his presidency will greatly hinge on whether he can avoid being broken by it.

In turn, the 2012 presidential election is also a political watershed. As was pointed out earlier, it marks the first time in 17 years that the country will be ruled by a Socialist President and the first in ten that a Socialist government will decide policy. Should the parliamentary elections go as expected, a healthy Socialist majority is likely to be returned to the National Assembly, giving Hollande the maneuvering room to pursue his agenda. On its face, such a development is to be welcomed because represents an alternation of power that is synonymous with the healthy functioning of democracy. Yet, there is also cause for concern, notably regarding the consequences of the parliamentary elections for the French Right. When considered on the backdrop of Sarkozy’s defeat, Marine Le Pen’s record score of 18% in the first round of the election could signal a seminal recomposition of the Right as a number of UMP candidates decide to participate in voting lists headed by the Front National in order to ensure their electoral survival, a strategy that is incidentally backed by two thirds of Sarkozy voters. Since Marine Le Pen came first in 23 constituencies and second in 93 in the first round of the presidential election, while garnering the 12.5% vote minimum required to participate in the second round run-off in 353 of 577 constituencies, it appears virtually certain that, for the first time since 1986, the Front National will gain parliamentary representation and be in a position to influence policy.

Regrettably, Nicolas Sarkozy bears considerable responsibility for this turn of events. By pandering to the Front National since the 2007 election campaign and through his term of office, he has legitimized the party’s xenophobic anti-immigrant discourse while affirming its exclusionary and essentialist conception of French national identity. This process reached a new nadir following the first round of the presidential election when Sarkozy, in an attempt to woo the 6.4 million French who had voted for her, affirmed that Marine Le Pen was “compatible with the Republic” and the FN “a democratic party” like any other. In this sense, the most lasting—and dubious—legacy of Sarkozy’s one-term presidency may well be the ascent of Le Pen and the entrenchment of the FN as a prospective party of government over the coming years.

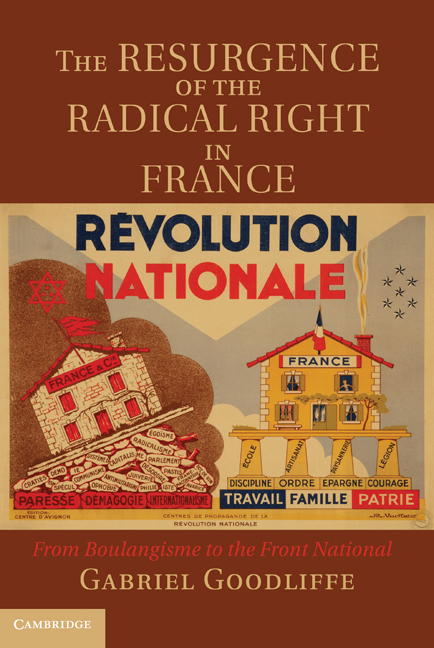

For Gabriel Goodliffe’s analysis of the first round of elections, see his previous entry.

Latest Comments

Have your say!