Autumn is most definitely here: leaves crunch underfoot; the air is crisp and cool; pumpkin and apple spices waft from the coffee shops. But while the season brings many changes, it does not alter work patterns dramatically for most modern people, though teachers might disagree. Of course, things were quite different in the agrarian society of early modern England, where the seasonality of labour loomed large. Our new Open Access book The Experience of Work in Early Modern England examines this subject of time-use, alongside many others central to social and economic history. The ‘Rhythms of Work’ chapter in particular asks how early modern worktime differed in its seasonal, weekly and daily experiences, and according to gender, occupation or employment status. This blog post offers a taste of the chapter and book (with just a hint of apple spice), as we take a brisk walk through the autumnal experience of early modern work.

The book is the collaborative and co-authored fruit of over a decade of research, across multiple projects led by Jane Whittle at the University of Exeter. It is based on a dataset of nearly 10,000 ‘work tasks’ spanning northern, eastern and south-western England, 1500 to 1700. We have collected these incidental references to specific work activities (and any ancillary information) by reading tens of thousands of witness testimonies from England’s church, criminal and coroners’ courts. These depositions yield incredibly rich vignettes of everyday life; our book blends qualitative readings of these narratives, with quantitative analysis of the work tasks extracted from them.

Almost exactly ten years ago, Mark Hailwood wrote a blog post exploring Autumnal Gatherers and Cider Makers, based on work tasks collected in the very early stages of our research. He raised questions about the gender division of fruit picking and cider production, and our project’s potential to shed new light on such subjects in the future. It seems fitting to return to this subject now. And appropriately, the ‘Rhythms of Work’ chapter opens with an anecdote about apples, cider and other autumnal labours in seventeenth-century Cheshire.

Margaret Johnson of Handley, the wife of a butcher named Ralph, had neighbours over for a drink in late September 1662, selling perry (pear cider) from her house. The sixteen-year-old servant Thomas Stockton out-drank his money, but paid back Margaret later on St Luke’s Day (18 October) with some apples and pears. Margaret accepted these, but ‘for fear of her husband’, had Thomas leave them in a shed instead of the house. As later revealed, Thomas had stolen the apples from his master (thus prompting the court case), though Margaret apparently did not know this when she received them. One week later, in the early hours of Saturday morning, she stored the fruit in the loft secretly while Ralph looked out the horses and cart. Together, husband and wife cut down and prepared their butcher’s meat, before transporting it to market day in distant Chester.

The episode is flush with time-use details, more than can be discussed here; it features early morning work in the dark or candlelight; workweek patterns pivoting around Saturday markets; people labouring on legal holidays. And it speaks to some of the work closely associated with autumn in early modern England and its gendered dimensions: fruit harvest; the storage and processing of produce and other foods (like meat); and commerce.

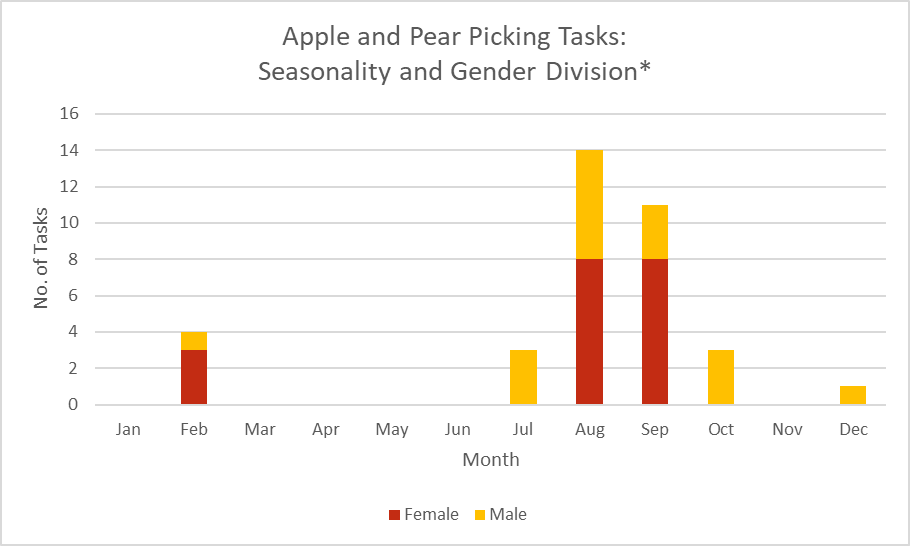

Figure 1

* Harvest additions and monthly weights applied; Integral included; Female adjusted (x2.58). See Ch. 1 and Ch. 4 for adjustment details.

For the purposes of our seasonality analysis, the autumn quarter runs from October to December. But as Figure 1 shows, most of our apple and pear picking tasks occurred in August and September, trailing off in October. We don’t know if Margaret or Thomas Stockton were directly involved in such picking, but our data suggests a near fifty-fifty gender division in this type of labour. The tailor Thomas Clarke testified in 1681, for example, that ‘sometime since apples were growing upon the trees this year’ [in August], he, his wife and son had been ‘gathering of apples’ together in one Mr Master’s orchard in Cloford, Somerset, when they heard information pertinent to a matrimonial church court case.

Once the fruit was in storage, it could be turned into cider. We recorded just four cider production tasks, all done by Devonshire men. But the qualitative richness of testimonies can help with quantitative limitations. Margaret’s involvement in cider production is never explicit, for instance, but it is heavily implied by the sale of perry from her house, combined with her acceptance and storage of apples. Keeping her husband in the dark, though perhaps tied to the apples’ suspicious origins, also suggests a degree of independence to her enterprise. Women’s connection to cider production comes through elsewhere in the dataset: nearly all buying, selling or serving of cider was done by women (89%), while women dominated the malting and brewing work category (80%).

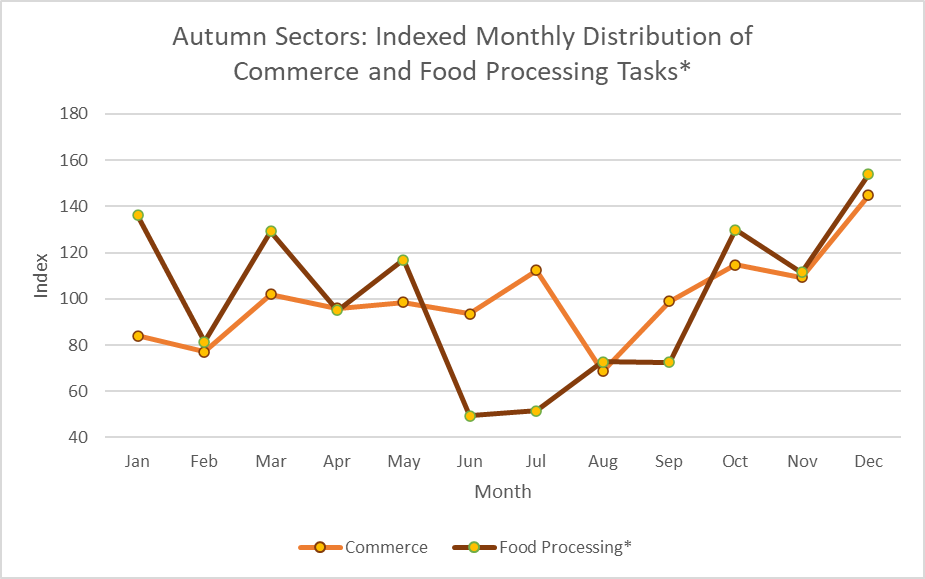

Malting and beer brewing could take place throughout the year, but it had a definite autumnal flavour; tasks clustered between September and November. This was part of a shift in focus from the cultivation and harvesting of food in the summer half of the year, to its processing in the winter half. As Figure 2 shows, food processing rose to a crescendo in the autumn quarter, underpinned by brewing, threshing and winnowing, and corn milling, but also slaughtering. Butchery tasks were at their height in these three months (38%), and could in turn prompt a flurry of transport and commerce. Butcher William Cubbech, for instance, purchased a heifer in Setchey market, Norfolk in November 1674, before droving it home for slaughter and sale at Lynn market in December.

Figure 2

* 100 = monthly average. Harvest additions and monthly weights applied; commerce excludes integral tasks; food processing reflects raw numbers. See Figure 4.3. Female adjusted for food processing (x2.58), commerce (x2.36). See Ch. 1 and Ch. 4 for adjustment details.

As this episode hints, market activity reached its zenith in the autumn quarter, with a December peak for the buying and selling of most types of goods, and not just livestock. Men and women, like Ralph and Margaret, shared fairly evenly in this commerce, though the former were more likely to contract the pricey livestock exchanges. Beyond commerce, women might generate income for the household through food and drink provision, as with Margaret’s perry party. Autumn ushered in a busy festive season for such social events; and commerce, food processing and provision all hinged around the frenzied Christmas season. One Cheshire miller summed up the mania in 1622, explaining that he never slept in his corn mill, except from ‘about a fortnight before Christmas because of that time there is much grinding’.

Grinding teeth might be more apt for modern Yuletide consumers, but the hectic holiday season sounds relatable nonetheless. With it, the early modern autumn came to a close. This season had much to keep people busy, in contrast to the old narrative of a lax and lazy cold half of the early modern economic year. And as our work-task approach illustrates, both men and women played crucial and overlapping roles therein.

In this way The Experience of Work seeks to capture the contributions of all workers and types of labour in early modern England, engaging with major debates about the preindustrial economy and shining new light on the contours of Tudor and Stuart working life.

Public Domain Image: Labors of the Months. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence. Image Description: Late 17th-century English needlework showing typical labours of the month. Focus shows a woman picking apples in October, and a woman spinning in November.

Latest Comments

Have your say!