Southern Africa is in the news: South Africa’s recent elections have seen the ruling African National Congress lose its majority in parliament for the first time since apartheid ended in 1994, producing a much more volatile political scene, while Zimbabwe confronts ongoing economic turmoil, and an armed insurgency continues in the far north of Mozambique. More threateningly still, across most of the region this summer’s El Niño-linked drought is a reminder of the growing challenges to food security and ecosystem stability that are driven by global heating.

In the face of these challenges, one of archaeology’s great strengths is its ability to combine a focus on people with an appreciation of the environments in which they live, exploring change in both – and in the interactions between them – over timescales inaccessible to other disciplines. This combination makes it particularly useful for understanding the complex histories out of which southern Africa’s contemporary political, economic, and ecological situation has arisen. One of the reasons for writing an updated edition of The Archaeology of Southern Africa was to convey a sense of those histories and of how archaeologists have come to learn about them.

But why should readers outside southern Africa want to learn about its archaeological record? The answer is because its past holds global significance. After East Africa’s Rift Valley, humans and their ancestors have lived there longer than anywhere else on the planet, with sites in the Cradle of Humankind near Johannesburg preserving some of the oldest hominin fossils we have, from both before and after the evolution of the genus Homo. Indeed, in the form of a 3.67-million-year-old individual dubbed ‘Little Foot’ they include the most complete australopithecine skeleton ever found. Concentrated near or on South Africa’s coast, though complemented by rapidly increasing work further inland, excavations at much more recent sites provide some of the earliest and richest traces of the cognitively complex behaviours particularly associated with our own species, Homo sapiens: jewellery, art, the controlled use of fire to manufacture complex adhesives or work stone, and archery, among many others. Fittingly, southern Africa’s Khoe-San-speaking peoples, who descend from the populations responsible for this evidence, belong to one of the most ancient human lineages of all.

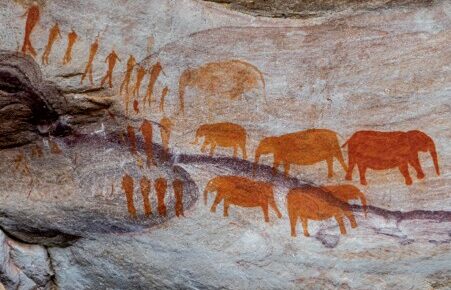

Ethnographic fieldwork among those Khoe-San groups who until recently still practised a hunter-gatherer way of life in the Kalahari Desert has proven foundational to how anthropologists understand mobile hunter-gatherer peoples worldwide. Archaeology gives us insights into how old those ways of life are and how they have changed over time, something that is particularly important because our ethnographies, while rich, are all recent and limited to just the driest of the many different biomes into which southern Africa is divided. Working back and forth between ethnographic data and archaeological materials enriches both disciplines, most of all perhaps in understanding the thousands of paintings and engravings found across the region. Largely concerned with the experiences and actions of shamans in altered states of consciousness and with beliefs about how to maintain correct relations with the animals on which people depended for food, these images form one of the world’s richest hunter-gatherer rock art traditions.

For the last 2000 years or so, and in a way difficult to parallel anywhere else, hunter-gatherers have increasingly shared the southern African landscape with societies practising other kinds of subsistence economy: pastoralists, farmers, and – ultimately – settlers of European origin. Today, it is their descendants, especially those of the Bantu-speaking farming communities who began moving into the region from the north in the early centuries AD, who form the bulk of southern Africa’s inhabitants. As a critical source of information for enhancing knowledge of this component of the region’s past, archaeological data reveal a rich history of emerging social complexity and eventual state formation, best, but by no means uniquely, observable at the famous site of Great Zimbabwe. In explaining how such farming societies developed and changed so swiftly, archaeologists turn increasingly not only – as in the past – to trading connections with the broader Indian Ocean world, but to indigenous African strategies of political action. This emphasis on the agency and innovative capacity of African populations also carries forward into their growing enmeshment since AD 1500 with European colonial expansion and the spread of global capitalism. As part of this, southern Africa now stands at the forefront of efforts to decolonise the archaeological discipline itself.

Writing this second, thoroughly revised edition of a book that first appeared in 2002, this was one of the many changes that struck me, along, of course, with the sheer increase in evidence and changes in ideas that have characterised the past quarter of a century. Prefacing my account with background chapters that look first at the geographical, ecological, and climatic frameworks on which writing about the region’s archaeology inevitably depends, and then at how the history of research has itself changed over the past 170 years, my preference has been to take things as much as possible in chronological sequence. Hopefully, this allows readers to see how things unfolded over time, while drawing them away from longstanding foci on areas like the South African coast to engage with the increasing diversity of research being undertaken elsewhere and simultaneously providing a reasonably comprehensive synthesis of more than three million years of human (and hominin) endeavour. Hopefully, too, the fact that all the illustrations I have used appear in colour wherever this was possible gives a clear sense of what southern African landscapes, sites, and artefacts actually look like.

Three weeks from now I shall be speaking at the opening of the biennial meeting of the Association of Southern African Professional Archaeologists at the National University of Lesotho. Forty years on from the start of my own involvement with southern Africa’s archaeology, I look forward to this opportunity of reconnecting with colleagues – especially new, early career researchers – learning still more about the region’s past, and being able to express my thanks in person to everyone in Lesotho who has helped me, and my students, conduct fieldwork there. Above all, I anticipate discovering how much has changed and how much new knowledge has been acquired since I delivered my manuscript to CUP a little under a year ago – and how much southern Africa’s past remains an essential tool for understanding its present and planning for its future.

The Archaeology of Southern

Africa by Peter Mitchell

Latest Comments

Have your say!