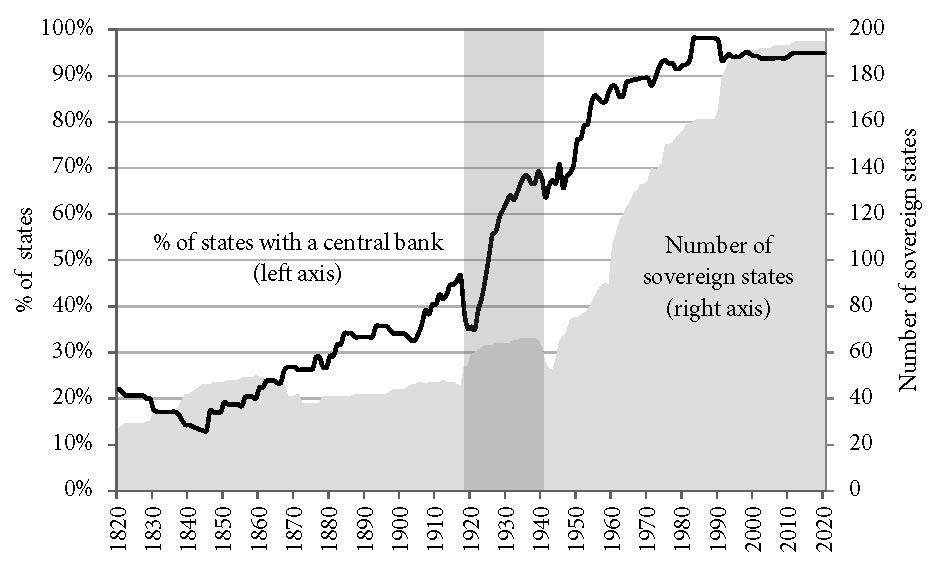

Central banks have not always been as ubiquitous or as economically and politically prominent as they are today. A century ago, some two-thirds of the world’s countries didn’t have one at all (see chart). Those who did took them less seriously: their functions were circumscribed, their mandates ambiguous, their allegiances divided between their commercial and state-sponsored activities.

And then something changed. Between 1919 and 1939, twenty-eight new central banks were set up, most in what are now called emerging markets and developing countries. The two decades between the First and Second World Wars were a key period in their emergence as players on the global stage. In The Spread of the Modern Central Bank and Global Cooperation, 1919-1939, we and our contributors provide a new account of their origins and early performance. By shifting the focus away from advanced economies and prominent central banks, our account complements and at time challenges the conventional historical narrative about the evolution of central banking.

Substantively, we show how that early experience led to the subordination of central banks to governments after the Second World War, followed by their gradual recovery of autonomy – or independence,” as it was now known – in the final three decades of the 20th century. Methodologically, our volume contains both synthetic cross-country comparisons and national case studies. Together they document how the institutional arrangements shaping the monetary and financial policies of these central banks were influenced by the leading central banks of the period, the Bank of England, Bank of France and U.S. Federal Reserve System, which sent financial experts, known informally as “money doctors,” as emissaries to advise on the design of monetary statues and practices.

Not unexpectedly, these experts advised leaders to design their new monetary institutions along the same lines as those of the central banks that organized and commissioned their visits, in reflection of what the monetary experts in question saw as best practice and but also to encourage practical and intellectual links with the sponsoring country and central bank. Typically, this advice centered on the desirability of adhering to the gold standard, this being practice in the leading central banks in the period. It emphasized the importance of independence from government (“autonomy” in contemporary parlance), with a view to limiting pressure on the central bank. It also signaled an attempt to remove monetary policy from the domestic political arena, just when the extension of the franchise had made the latter more representative. In a theme that is both recurring in the book and reminiscent of more recent challenges, this process of de-politicization turned out to be very political, both in its motives and its distributional consequences.

Design of these new institutions was further influenced by international institutions, most notably the League of Nations, which dispatched monetary experts of its own. The League’s advice proved hard to resist, especially by newly independent countries in Central and Southeast Europe, since the recipients were desperate for League-sponsored stabilization loans in the aftermath of the First World War. The League’s monetary missionaries emphasized that stabilization loans required the recipients to agree on fiscal stabilization, gold convertibility and central bank autonomy. Loans and reforms were effectively part of the same package, anticipating the role – and many of the limits – of conditionality in International Monetary Fund “stand-by” loans and similar post-war arrangements. The Bank of International Settlements (BIS), established in 1930, in part, to anticipate the activities of the Bretton Woods institutions, while acting as a central bankers’ bank. Yet in the fraught diplomatic environment of the 1930s, this was easier in theory than in practice.

The Great Depression that set in after 1929 and the global financial crisis that erupted in 1931 were the crucible for interwar central banks. New central banks, like their older predecessors, were forced to choose: they could either defend the exchange rate at the expense of economic activity; or they could accommodate the needs of the economy and financial system at the cost of abandoning the gold standard. They took the orthodox route at first, hoping to retain, or in some cases regain, access to foreign capital. But as the trickle of foreign capital dried up entirely, the position became untenable, and they began leaving gold – in small numbers initially, and then en masse following the pound sterling’s devaluation in September 1931.

Departures from gold took different forms in different countries: devaluation in some cases, capital and trade controls in others, and regional clearing arrangements in still others. How central banks reacted, or in some cases failed to react, depended not merely on their statutory independence but also on the broader network of institutions and political and societal relations in which they were embedded. It depended on shared ideas and experiences, notably historical experiences, that shaped their decisions and policy actions.

In some cases, attempts to relax the tradeoff between external stability and internal reflation helped to ameliorate the worst of the Depression; in others they were less effective. But in all cases there was a departure from the advice of 1920s money doctors. In this sense, the Great Depression forced a fundamental re-think of the role of the central bank in the economy.

In a majority of cases, in addition, the failure of central banks to prevent the economic and financial catastrophe of the Depression undermined political support for their autonomous operation. Their decisions informed by this failure, governments reclaimed powers that had been delegated to central banks. In Britain, there was a subtle “redistribution of authority and responsibility” from the central bank to the treasury (in the words of the Bank of England’s Governor, Montagu Norman). In the United States, the change was codified by legislation (the Thomas Amendment and the Banking Act of 1935). Central banks in emerging markets followed suit, returning their recently acquired powers to national governments. Governors were replaced; statues were revised. Autonomous central banks were effectively nationalized.

With government control came greater policy activism. Even orthodox money doctors such as Edwin Kemmerer of Princeton University, a long-standing apostle of the gold standard, having been chastened by the Depression, nudged central bankers toward greater activism. Central banks belatedly embraced their role as lenders of last resort; their new activism extended to prudential supervision and bank regulation. They underwrote import-substituting industrialization what increasingly began to resemble centrally planned economies.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, this transformation was complete. Fiscal dominance, meaning that monetary policy was subordinated to the imperatives of financing the government, became the order of the day. Acute dollar shortages then again threatened postwar reconstruction, and central banks were again enlisted to provide money finance. Interwar history – monetary instability followed by the superimposition of monetary orthodoxy in response – seemed destined to repeat itself.

But this time was different. Informed by memories of interwar experience, reparations and war debt were minimized. The United States provided generous finance for Europe’s trade deficit via the Marshall Plan. Exchange rates were re-pegged, but this time they were made more adjustable, and capital controls were authorized to shield countries from destabilizing capital flows. Central banks continued to coordinate closely with governments, while also expanding their range of responsibilities and interventions.

In this new postwar environment, central banks were less independent but more poweful. Emphasis on state intervention and economic modernization in the third quarter of the 20th century meant that central banks established in the 1920s and 1930s now became instruments of development policy. Their role was to support efforts to allocate credit and to target industries in pursuit of economic growth. In this, they were joined by another wave of post-colonial central banks.

The coda came finally in the 1980s and 1990s, as additional reforms were put in place in response to the failures of these credit-allocation and targeting policies, and specifically in response to the problem of unacceptably high inflation. These reforms included renewed emphasis on the virtues of central bank independence, implemented through statutory changes and in some cases the adoption of explicit inflation targets. For those with a historical sensibility, this was a true back-to-the-future moment.

Such is the nature of central banking today. Central banks emphasize their commitment to inflation targets while coming under pressure from their governments to help manage public debt (with the associated danger of “fiscal dominance”). They are increasingly tasked with macroprudential and microprudential supervision. They are encouraged to cooperate, even if they don’t always succeed in practice. And they are increasingly relied upon to override political deadlock and provide apolitical, technocratic solutions, to what remain inherently political issues with important distributional consequences. The interwar years anticipated this contemporary paradigm and many of its challenges. A look back at that history, through the lens of our volume, sheds light on the circuitous route by which we reached this state of affairs – and on how events may play out from here.

Latest Comments

Have your say!