Months before the United States entered the war, American men, women, and children mobilized to “adopt” France’s orphans. Through a binational humanitarian relief organization known as the Fatherless Children of France Society (FCFS), Americans provided for the material needs of some 300,000 orphans across France between 1915 and 1921.

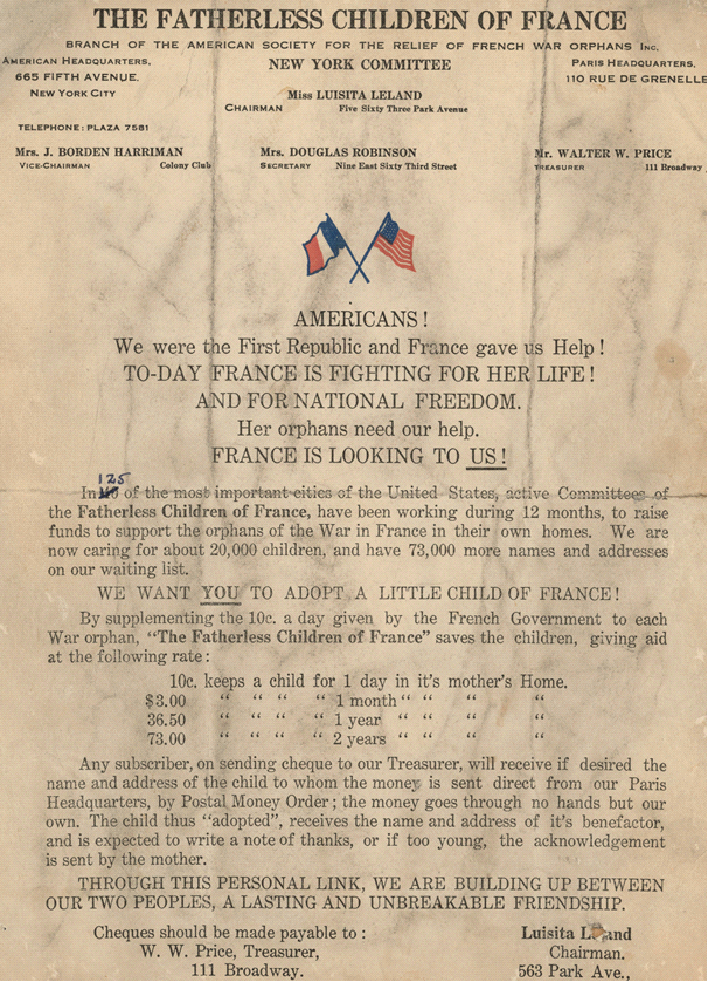

Founded in 1915 by Émile Deutsch de la Meurthe, a Jewish Paris-based industrialist, the Fatherless Children of France Society (FCFS) was envisioned to support boys and girls whose fathers had been killed in the war. The campaign used the terms orphan to denote the fatherless and adoption to describe the commitment to send funds on a regular basis (under no circumstances were French orphans going to be shipped to the United States). From New York City, with committees across the United States, the Franco-American private philanthropic organization raised a rapid wave of humanitarian response, doing so through strategic communication and tireless networking. Much of the campaigning was done by women. Members of the FCFS toured US cities, states, and territories, opening chapters and addressing assembled crowds, constantly collecting funds. Speakers vividly described the plight of starving babies in devastated France. In 1918, with 140 local units scattered across the United States, Americans of all backgrounds had already adopted more than 60,000 French orphans. By 1921, this binational humanitarian relief organization had provided financial and material support for some 300,000 orphans across France.

Unsurprisingly, individual initiatives from wealthy Americans shot up across the United States to protect France’s future generations. Cultural and leisure events greatly helped the organization raise funds. Wealthy individuals organized private performances, parties, sports competitions, and other activities. A golf tournament in St. Paul, Minnesota, for instance, raised $3,000. In Cincinnati, Ohio, a Zoo Fête netted more than $29,000 for the orphans. A donation of $36.50 a year (the equivalent of $978 today) was all that was needed to sponsor a child for a whole year, and only children under sixteen were eligible to be cared for by the FCFS. All could not, however, afford to give unpaid work to sponsor foreign orphans. But the Fatherless Children of France Society successfully reached the wealthy, middle, and working classes alike. American working-classes pooled resources to contribute to the protection of France’s future generations. In Bessemer, Alabama, hundreds of workers subscribed one hour’s pay, and collected enough money to adopt 135 orphans. An original idea from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, permitted workers and families with a modest income to contribute: collecting rubber. Members displayed a big sign in a prominent position, reading “Leave Your Old Tires Here for the Benefit of the Fatherless Children of France.” Locals hunted up all the old casings of the county cars. This is telling given that working-class families tended to have a more “instrumental” (as opposed to “sentimental”) view of children. For working-class groups, feeding an additional mouth in France entailed an even greater sacrifice. Consequently, the history of French orphans adopted by American “godparents” challenges the traditional patterns of humanitarian-based interventions. While prominent members of American society and local communities may have coordinated humanitarian action at the state and federal levels, working-class men, women and children did their part (certainly to a lesser extent) in sponsoring starving orphans in France. American women (and men) from all social backgrounds built the FCFS into viable, visible nationwide relief organization.

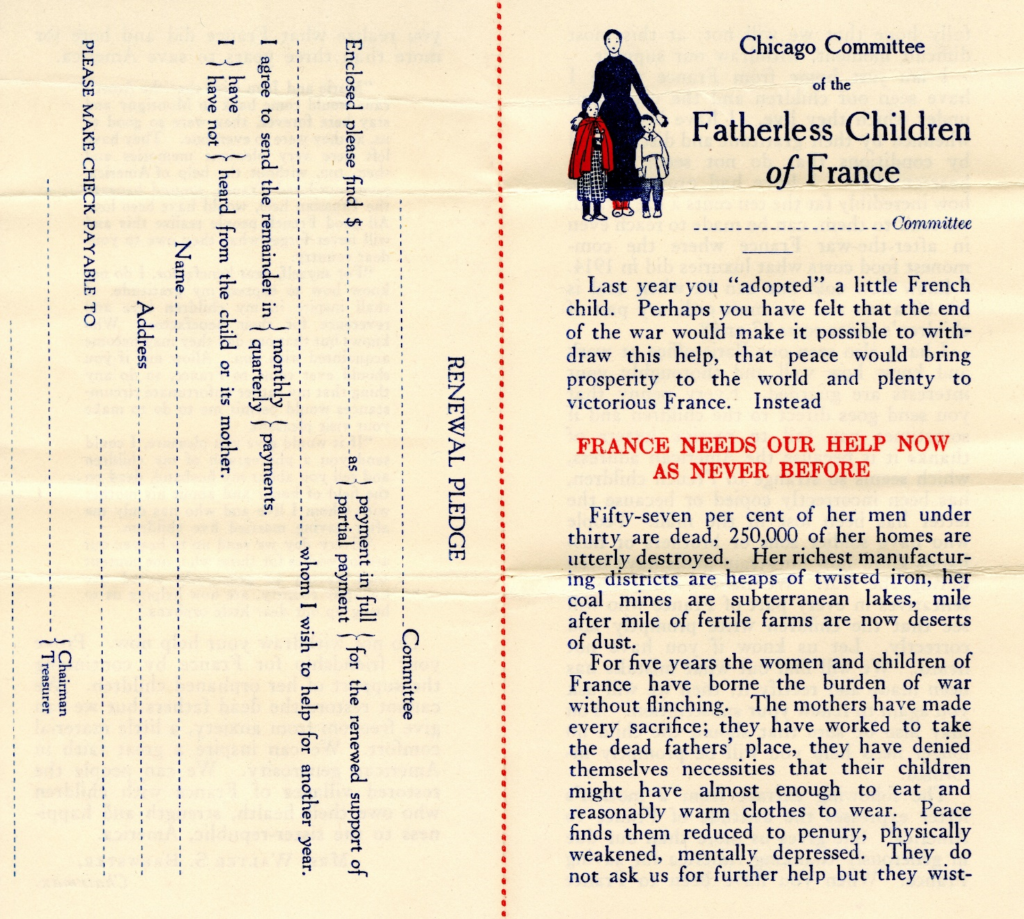

What was crucial in mobilizing American godparents was the appealing aspect of being involved in the process of selecting their orphans. Americans were offered a choice in how to spend their humanitarian dollars. While organizations like the American Red Cross collected money to engage in a wide range of humanitarian operations, people rarely knew exactly how their contributions were being used. Conversely, the FCFS connected American families with specific French children and families with whom they could correspond. They gave contributors an opportunity to hear about the impact their dollars were making on individual lives, which was an effective way to encourage still more contributions. In providing Americans with a choice in how to spend money the FCFS spearheaded a new form of humanitarian assistance that would develop globally in the aftermath of the war. Americans chose the child by location, age, and gender. The choice hinged on a similar name, a similar birthday, or a familiar locality. Wealthy American women opted to choose an orphan with the same birthday as their own biological offspring. Sometimes, having the same first name as an American’s child could be enough to save a French orphan from destitution. American workers wanted to sponsor the sons of France’s working classes. Rural godfathers and godmothers tended to choose orphans living in the French campagne. A group of women working in a big department store pooled resources to “adopt the child of some worker in the big Parisian stores.” A process of identification, a search for a connection rather than a simple desire to rescue a destitute child often guided the adoption process. In short, personal, social, and economic considerations played into sponsorship.

Choosing to donate to the Fatherless Children of France Society entailed that Americans knew exactly what their dollars would be used for. Unlike other humanitarian organizations with a transnational or global reach, the FCFS positioned itself directly and solely for the relief of France’s children. It never sought to address the destitution of other foreign children or civilian populations. This is why it can be rightly argued that in the mind of some Americans, donating to the FCFS could be a means to counter the United States’ official policy of neutrality. In helping to financially support France’s beleaguered children, Americans could (if they wanted to) evade their country’s neutrality and express a political preference for a French victory over Germany. The American Red Cross, for instance, initially vowed to assist the sick and wounded soldiers of all nations, refusing to have anything to do with noncombatant relief. On the contrary, in deliberately assisting noncombatant, and especially fatherless children of a single country, the FCFS dissociated humanitarian relief and neutrality, as it clearly attested the choice on the part of Americans to help what, by April 1917, would be an Allied nation.

What can also explain the attractiveness of the Fatherless Children of France Society was its ability to mobilize American children. It was certainly not the first time in the history of humanitarianism that children were engaged in humanitarian efforts. During the American Civil War, for example, children participated in humanitarian actions run by the US Sanitary Commission. In the abolitionist movement, children played an important part in combating slavery and racial discrimination. Consequently, rather than pointing to the novelty of the phenomenon, it is wiser to maintain that the scale of children’s involvement with humanitarian work escalated during World War I. When the New York City headquarters of the FCFS opened a junior division in October 1916, months before the creation of the Junior Division of the American Red Cross, the FCFS had already developed its strategy to incorporate American children into the humanitarian cause. In schools, churches, and clubs, they organized fundraising and pooled resources to adopt a “brother” or “sister” in France. Some wealthy children “got a French child as a birthday present,” while working-class boys and girls went in together to sponsor a single orphan. The experience of sponsoring an orphan through the FCFS reinforced a sense of citizenship. That was revolutionary. Caring for France’s orphans was an invitation to American children to contribute to the war effort while learning (albeit indirectly) what such a terrible catastrophe had wrought. The marketing strategy and campaign materials gradually and gently introduced American children to the harsh consequences of the war, through the experiences of Europe’s children. American children might not be exposed to visual depictions, as newspapers refrained from publishing overtly explicit displays of sufferings, but they could apprehend, talk about, and discuss the realities of war with their teachers and parents. Inviting American children to reflect upon the sufferings of French orphans was seen as a way to boost their patriotism, cement a feeling of national duty, and educate them. Before US entry into the war, the FCFS functioned as a vehicle for the transmission of humanitarian values, inculcating American children with ideals of altruism, patriotism, and moral activism.

World War I undeniably ushered in a new era of involving children in US foreign policy initiatives. In the aftermath of the war, initiatives such as the Near East Relief (1919), Save the Children Fund (1919), and Save the Children International Union (1920) multiplied. On the model of the Fatherless Children of France Society, Save the Children Fund asked donors to “adopt” a German, Polish, or Russian child for two shillings a week. Other organizations similarly requested sponsorship of Armenian children and Serbian children. At the international level, the League of Nations concerned itself with the health, safety, and protection of youth. Over the years and decades to follow, the League of Nations, United Nations, and State Department ran programs to promote global fraternity by placing diverse young people in contact with one another. Civic and religious organizations such as the Rotary Club, Friends Service Committee (Quakers), and others developed student exchange programs. But the reality is that with the loss of some many men on the battlefields, a generation of children grew up in the shadow of their departed fathers. The FCFS’s focus on fatherlessness mirrored contemporary social concerns that a child growing up without a role model in the household might not be properly educated, schooled, and guided by masculine values. Fathers were considered guardians of their daughters’ sexual purity, honor, and social standing and were expected to model masculinity for their sons. “Godfathers” could help fill a void, as could “brothers.” But correspondence, gifts, and money would never fully compensate for the absence of a father. And loss felt by all these fatherless children in France, and elsewhere in Europe, cannot properly be voiced by the archives of any humanitarian organization.

Poster from the Fatherless Children of France Society, 1918. Albert J. Earling Papers. Wisconsin Historical Society Library and Archives, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Coupon from the Fatherless Children of France Society, 1918. Ladies Literary Circle of Dwight, Minutes 1918–1920. Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, Springfield, Illinois.

America’s French Orphans

by Emmanuel Destenay

Latest Comments

Have your say!