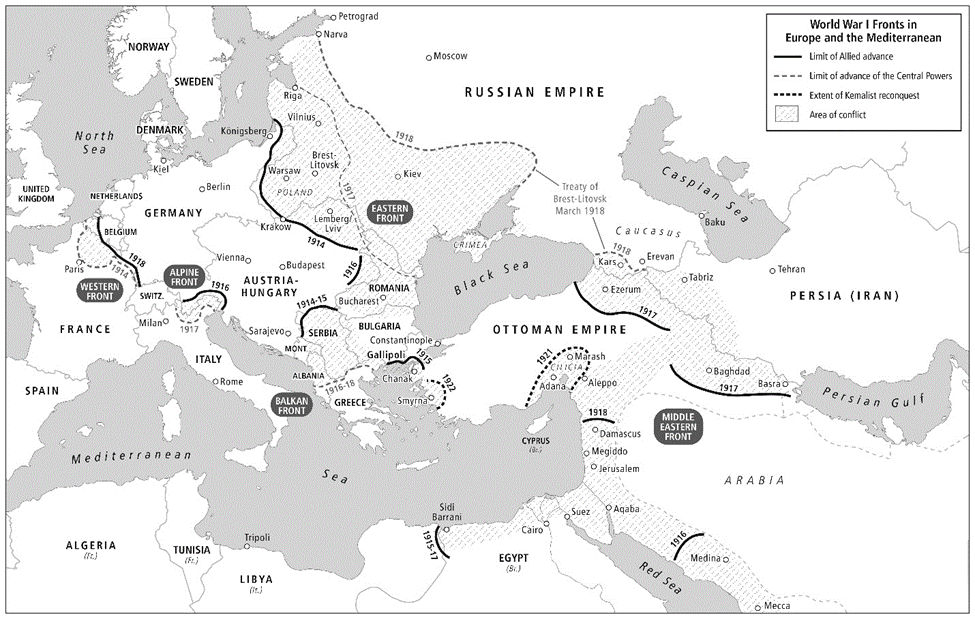

The First World War was a war of empires that started in the Balkans and ended in the Middle East. Yet, some historians still see this war as a mostly European story. Mapping the different fronts of the war together challenges this perspective:

I wrote The Last Treaty, in part, to understand why war historiography has segregated fighting in the Ottoman Empire from Europe. In reality, the Middle Eastern and Western Fronts mirrored one another.

Trench warfare happened on both fronts at the beginning but, by 1917, gave way to a war of movement in Mesopotamia where quick decisive victories led to the signing of the first armistice with the Ottoman Empire in October 1918. Both fronts also saw the blurring of the relationship between home and battlefront. Civilians helped determine how the war was fought and won on the Middle Eastern Front just as they did on the Western Front. Belligerents mobilized their economies to produce weapons, food and resources to fight the war due to the demands of industrial warfare. New ways of seeing civilians in wartime emerged. On the Middle Eastern and Western Fronts, news of the brutal treatment of non-combatants justified war in Europe. The call to defend civilians targeted by the Armenian Genocide in spring 1915 echoed the Belgian Atrocities used by Britain to validate its entry in the war in August 1914. In both cases- the treatment of Christian minorities by their own government in the case of the Ottoman Empire and the treatment of Belgian civilians by the invading German forces- the defense of the rights of others gave the war a just cause.

Mapping this space as “Middle Eastern Front” rather than “Ottoman Front” better incorporates it into the lexicon of the First World War. “Ottoman Front,” the term often used by Ottoman historians, denotes the belligerent rather than the geography of a war that was defined as much by location as anything else. Designating fighting that took place among the Allies, Germany and the Ottoman Empire as the “Middle Eastern Front” parallels the use of “Western Front” and “Eastern Front” that also are problematic. For example, the Western Front refers to fighting in Belgium and France but, as the above map of war fronts shows, the area shifts over the course of the war. The same goes for the Eastern Front regarding fighting along the Russian border. The Balkan Front and the Alpine Front equally resist clear definition.

While these borderless fronts lack precision, such regional designations spatially map the war to coincide with the political geography as imagined by belligerents at the time. Western Front and Eastern Front continue to be especially meaningful designations that orient the work of war historians. Analyzing multiple fronts- Western, Eastern, Middle Eastern and others- bounded by rough geographical designations deepens our understanding of the First World War as a war of alliances. The Ottomans fought with the Germans on the same front together as allies. To call this the “Ottoman Front” obscures this important relationship.

The Middle Eastern Front’s integration into the war’s geography renders visible colonial relationships embedded in the deployment of the term Middle East in the early twentieth century. Not naming this front in accounts of the war by European historians has contributed to an act of erasure by using clumsy nomenclature to designate fighting here as a separate set of actions. Denying a geography for this front, however hard to outline in terms of actual territory, renders it less visible to the larger action of the war than the “Western” and “Eastern” fronts that suffer from a similar lack of clear physical boundaries. Maps, correspondence, film and photography- the representational apparatus deployed by Europe’s generals, strategists, soldiers and diplomats engaged in this theater of war- defined this space of engagement. For the British, the idea of the “middle” and “near” East were relational colonial terms that denoted Britain’s distance from its empire in India. As I have shown elsewhere, a similar historical process of imagined geographical designation was at work in the nineteenth century when the British first deployed the term Near East to designate Christian-occupied lands on the borders of Europe as a way of mapping their empire.

Remapping the First World War in this way forces a rethinking of chronology and geography. Simply put, when the war ended depended on where you were. The Last Treaty focuses on how World War I ended. War and peacemaking developed as an overlapping set of processes that made continued interethnic and political violence a defining characteristic of the years leading up to the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies in 1923. The last treaty of the First World War marked the end of military and diplomatic processes set in motion by the war that had devastating consequences for civilian populations. Viewed from the rearview mirror of Lausanne, the Middle Eastern Front takes its rightful place as a crucial site in the war between empires.

Latest Comments

Have your say!