In my book on the birth of the psychoanalytic periodicals, I re-read favorite essays by Freud and Jung in the context of an entire issue in reverse chronological order (like Freud told us to do).

It was a religious revelation. I profess (this is my actual paid job) that Freud was a devoted servant to יהוה, the four-letter Tetragrammaton YHVH that people called either “Jehovah” or “Adonai” but that Freud pronounced AHAVA (in Hebrew “love”).

In 1906, Freud found C.G. Jung and other like-minded people in Zurich and Boston whom he could talk to about the sacred nature of LOVE. Naturally, they were predominantly Christians (which does not generate the same obsession with demographics that Freud’s predominantly Jewish circle triggers). The conversation, which began so impassioned if not downright messianic, ended in a classic Christian-Jewish disputation (and the concomitant dissolution of the Jahrbuch).

By 1914, Freud felt that Jung and his circle were driven by antisemitic prejudices they could not see themselves no matter how much ink he spilled on the subject. So, before Freud parted from Jung forever (depending on one’s attitude towards eternity), he took his case against Jung’s “future-oriented” Lutheran libido to the Pope in Rome. That is, Pope Julius II, whose tomb in the church of San Pietro is guarded by Michelangelo’s statue of Moses.

You can read all about it in Freud’s “The Moses of Michelangelo” (1914). The essay has generated more critical commentary than any other one in Freud’s oeuvre and holds the honor of being his most misunderstood piece of writing—so far eluding any scholarly consensus. Freud’s essay on Michelangelo’s Moses contains so many subterranean labyrinths of myth, metaphor, literature and religion that it almost feels impossible to contain all of its implications.

Luckily, in addition to all the contradictory and mutually exclusive words Freud composed, he gave them/us images to study. A photograph and four illustrations. But in order to understand them, you must interact with the original Imago issue (and several of its predecessors which provided the clues) in which it appeared both because of the paper quality and because small edits were made to every subsequent publication.

In his journal Imago, Freud was dealing with the debate on “signs” that was splitting his dispersed flock into little pieces. Freud’s camp and Jung’s camp, with the American camp watching on in interested horror, were struggling over the question of whether unconscious psychic material can be revealed from an external source or limited to the mechanisms of the individual psyche. I must state in advance that I make no attempt to answer this question. I can, however, show you what Freud did with “signs” in the essay, whose visual demonstration is contained in the four illustrations he commissioned and hand-edited of Michelangelo’s Moses.

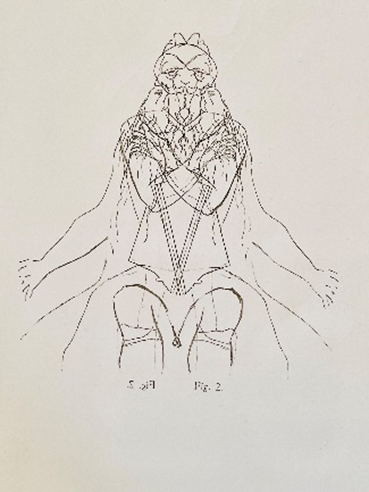

Freud’s answer to the question of the origins of psychic material is found in his four illustrations, which are also really eight, maybe 64. Freud’s illustrations are a paper puzzle, a form of game very popular in the nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries in Freud’s bourgeois milieu. The text in the essay gives readers strict instructions for how to look at the images, how to fold them, how to flip them over and push them towards one another.

Freud’s publication of a hand-maneuvering exercise sought to show readers how memory stores partial perspectives (visual signs) as whole. The pages of the original Imago issue in which Freud’s essay on Michelangelo first appeared are translucent enough to be held up to the window and cheap enough to be purchased in multiple copies (honestly, Freud was giving them out for free).

Following Freud’s explicit instructions, we gently flip one over each image and push it towards its doppelganger on the other side. The new image that magically emerges before our eyes is what Freud theorized to be a “thing-presentation,” the duplication of a perceptual sign that is then inscribed into memory as a whole image. If we follow Freud’s instructions and gently push each of the four images towards its “doppelganger” (its flipped over pair), we are rewarded with the frontal face of Moses from these three different and mutually exclusive perspectives.

When this procedure is followed with Illustration 1, one sees an image of the Hero-Prophet emerge from the merging of a profile and its inversed copy. Freud shows that this attitude on the part of Michelangelo’s sculpture has made its way into the annals of art history, citing to Fritz Knapps’ heroic visionary of the “huge frame” of Thode’s “Titan” and “superman,” Steinmann’s “royal priest,” whose “proud head” Herman Grimm saw “carried high on his shoulders.”

When this procedure is repeated with Illustration 2, we see what Freud’s citation to other art historians described as a hideous satyr. Here, we see Max Sauerlandt’s description of the great statue as an animal-like Moses “with the head of Pan” whose “brutality” is visible on “the animal cast of the head” as he sits, in Carl Justi’s words, “as an agitated man” left “quivering with horror and pain” that in Heinrich Wölfflin’s description depicts a figure consumed by “inhibited movement.”

If we move to Illustration 3, that is, to the image of Moses as seen from the FRONT of the statue, none of earlier impressions and emotions remain visible. In fact, our narrator confesses, nothing really happens at all. It was as if “the stone image became more and more transfixed, an almost oppressively solemn calm emanated from it.” When we complete the image Freud made in FRONT of Moses, sitting in the dead Center, we see the figure of a blank man.

But what about the final image? The one mislabeled, or so it seems, with a letter rather than a number. The last one (maybe the first one) was labeled “D,” presumably for Deus. Without a face, how did Freud’s readers know how to put it and its copy together?

It’s the fingers: the ones Freud borrowed from Michelangelo’s God reaching for Adam in the Sistine Chapel. As we slowly and intentionally bring the images closer to one another, the outstretched index fingers will begin to draw towards each other just like Michelangelo taught us to do about 500 years ago when he taught us the art of illusion. And when we do that…

…When we look at the reconstructed image of Freud’s G-d, we find a true believer.

While Freud wholly rejected Jung’s claims that psychic material is generated and implanted by an external source outside the individual Self, Freud’s images reveal a very serious and sincere attitude towards religion. In Freud’s faceless image, the Original Source is perfection. In Fig. D., each and every line is necessary. There are no lines to discard in order to see the illusion. The Source requires no fancy folding or manipulation. A magical transformation happens nonetheless: the knot of Moses’ beard unravels and a perfect divine energy emerges from The Source. Instead of knots, we find a beautiful force that emanates between the two fingers of the Creator. On each side of the beautiful energy that emanates from the center of the One Source lies what our narrator described as “a kind of scroll,” which once doubled creates the suggestion of a Torah scroll. The hands lie atop the Tablets but the Torah scroll emanates from the face of God.

We see a visual of a sun-like sphere rising to the horizon of the divine clavicle and sinking beneath the horizon of the divine waist line, below which it rests in a genital-like tripod containing BOTH SEXES. The bisexual nature of LOVE is more visible when you fill in the Divine force in the image of Man.

It is a revelation, the sort Freud believed in. For me, it felt like I gave one little Jew his God back.

Title: Freud, Jung, and Jonah

Author: Maya Balakirsky Katz

ISBN: 9781009100007

Latest Comments

Have your say!