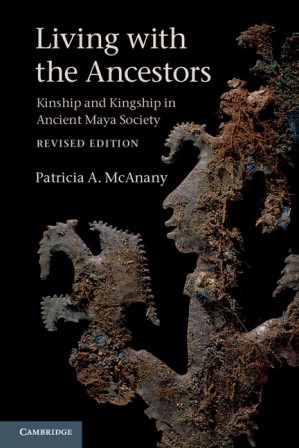

Portion of a magnificent K’awiil scepter—a metaphor of royal power through ancestry and also of fertility and agricultural abundance. This chipped stone eccentric (one of nine) had been carefully wrapped in Maya blue cloth and placed within a 6th century building at Copan, Honduras.

Life is stranger than nonfiction. While writing the first edition of Living with the Ancestors, my father died. Then a month before the revised edition was scheduled to appear, my older brother—a Vietnam War veteran—died very suddenly in St. Louis, MO. In the space of a few days, I was swept from the mundane world of end-of-semester exams in Chapel Hill, North Carolina to an Irish-American wake, a Catholic Mass with heart-rending eulogies, and a mile-long funeral procession to a military burial ground. On a snowy winter day, the funeral party gathered around an open-air limestone pavilion to witness a powerful mortuary ritual reserved for those who once were soldiers: a six-gun salute; folding—in a slow and meticulous fashion—the U.S. flag that had draped his coffin; and the anguishing finality of a bugler playing taps. “Day is done”…a life is done. As we listened to the haunting melody, the men stood very still; most of the women—including me—sobbed uncontrollably. Strangely the effect of witnessing (and hearing) the funeral ritual seemed both to magnify the hole in my heart created by the loss of my brother and also to heal it a little. The snow continued to swirl around us as we left the pavilion and returned to the parish church where a hearty lunch of St. Louis-style pasta (mostaccioli) and local brew awaited us.

You might be thinking: I am sorry for your loss but what does this story have to do with the revised edition of Living with the Ancestors? Everything. Life is about loving and ultimately losing to the unassailable forces of mortality those we hold dear. This claim holds true whether we live in the transglobal world of the 21st century or the more closely framed world of pre-colonial times—as a resident of a Maya dynastic city or smaller town. The grief and loss felt so acutely by survivors is no different but how we respond to death as a social collective is deeply contextualized within space and time. Deathways—the social practices that are elicited by mortality—provide a vivid demonstration of cultural diversity and often of social differentiation within a group. Both are evident in the funeral service for my brother.

When I first began archaeological fieldwork in the Maya region—on the Pulltrouser Swamp Project directed by Peter D. Harrison and B. L. Turner II—I did not understand the significance of residential burial and had no idea that I would spend so much time studying a social practice called ancestor veneration. After all, the project was focused on ecological questions about wetland utilization. Although our test units were only 1.5 meters on a side, we often encountered burial contexts as we excavated through nearly 2000 years of recursive construction activity at the dwellings placed on high ground surrounding the wetlands. Later when I returned to one of the ancient wetland communities for expanded excavations, I learned that dwelling renovation and burial placement often occurred hand-in-hand—perhaps indicative of inheritance processes at work.

By keeping the dead close by, critical tenets of social order seem to have been maintained. Yet the criteria for selection to become an ancestor-buried-within-the-residence remained elusive. During Preclassic times (1000 BCE to 300 CE), the remains of men and women and both children and adults were interred within residences. At K’axob bioarchaeologist Rebecca Storey found several burial contexts that contained the remains of adults plus infants and very young children—sometimes placed in the lap of the adult. Given the much higher incidence of infant and maternal mortality during pre-industrial times, I can only imagine the sorrow that accompanied those funeral interments.

Fellow Maya archaeologist Julia Hendon has written that the social practice of living with the ancestors likely created strong memory communities as descendants lived on and renovated dwellings directly on top of ancestor interments. This deep history of many Maya dwellings of the first millennium BCE and CE likely resonated in other arenas of life too. Life opportunities, social status, legitimacy of land claims, and political leadership might be linked to your ability to recite a genealogy that was materialized in ancestor interments. Seldom on display, the bones of ancestors were safeguarded within the residential compound much as we secret valuable heirlooms in a bank vault. The efficacy of these practices is suggested by the fact that Classic-period dynasties ramped up the importance of ancestors to the point of building massive funerary temples that equated memory community with polity.

Departing from the political and economic implications of living with the ancestors, archaeologist Susan Gillespie suggests that a religious belief in soul regeneration might account for the practice of residential burial. In effect, survivors were responsible for the safe storage of a corpse as the receptacle for a soul that might be revitalized in later generations—possibly in a grandchild. Linguistic support for this idea can be found among contemporary Mayan peoples of Guatemala.

No matter how you seek to explain it, deathways are a vital part of how we define ourselves as social beings. The cultural importance of these practices is the reason why I choose to publish a revised edition of Living with the Ancestors. As a group, we mourn the loss of family and friends and we take care to handle corporeal remains in a manner that is prescribed culturally. We learn to live with that feeling of loss—a new hole in our emotional core—and finally we look up and, haltingly at first, continue to live. The highly variable conditions of continuance depend upon our cultural context. Yet in the end, we all learn to live with our ancestors.

Latest Comments

Have your say!