The sixth post in The Horse in Human History blog series.

The ritual sport of buzkashi has traditionally been played by steppe tribes with the carcass of a goat, calf, or sheep. Whereas nowadays this equestrian contest is likely to be conducted in an urban stadium, on the steppes buzkashi was organized to mark a festive event such as a wedding or puberty initiation. The sponsor of the game was invariably an eminent personage, whose following at home would provide hospitality to the numerous participants. And his reputation was such that he would attract prestigious competitors from afar, bearing rich gifts to be awarded as prizes during the contest. The distinguished sponsor’s role was to maintain a demeanor of decorous hospitality. He was aided by a lieutenant, whose responsibilities were to umpire the game and to resolve any disputes that might erupt. Buzkashi thus facilitated at the regional level the periodic aggregation of nomads, habitually scattered over a vast area–a rare sort of gathering for such a population.

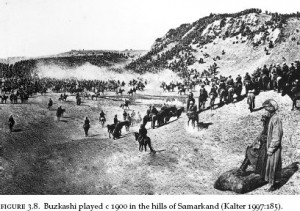

The ritual sport of buzkashi has traditionally been played by steppe tribes with the carcass of a goat, calf, or sheep. Whereas nowadays this equestrian contest is likely to be conducted in an urban stadium, on the steppes buzkashi was organized to mark a festive event such as a wedding or puberty initiation. The sponsor of the game was invariably an eminent personage, whose following at home would provide hospitality to the numerous participants. And his reputation was such that he would attract prestigious competitors from afar, bearing rich gifts to be awarded as prizes during the contest. The distinguished sponsor’s role was to maintain a demeanor of decorous hospitality. He was aided by a lieutenant, whose responsibilities were to umpire the game and to resolve any disputes that might erupt. Buzkashi thus facilitated at the regional level the periodic aggregation of nomads, habitually scattered over a vast area–a rare sort of gathering for such a population.

At the commencement of the game, the calf was ritually decapitated and eviscerated. Competitors often numbered in the hundreds, sometimes a thousand. Supposedly any player could position himself anywhere, but in practice only the tribal champions, backed by their retainers, through sheer  strength advanced sufficiently close to the center, where they were able to grab the calf. With the horses buffeting one another, their riders lunged toward the calf carcass. The struggle was most turbulent when the carcass was underfoot. On occasions two riders, seizing the calf simultaneously, might even rip it apart. In the ensuing furor, competitors brandished whips and drawn knives. The victor needed to wrest the carcass free of other horsemen and swiftly deposit it beyond the crowd, where his prize was awarded. At midday, a break was observed for spirited horseracing; at end of day, fierce competition ensued over final possession of the mangled carcass, a source of sanguinary pride.

strength advanced sufficiently close to the center, where they were able to grab the calf. With the horses buffeting one another, their riders lunged toward the calf carcass. The struggle was most turbulent when the carcass was underfoot. On occasions two riders, seizing the calf simultaneously, might even rip it apart. In the ensuing furor, competitors brandished whips and drawn knives. The victor needed to wrest the carcass free of other horsemen and swiftly deposit it beyond the crowd, where his prize was awarded. At midday, a break was observed for spirited horseracing; at end of day, fierce competition ensued over final possession of the mangled carcass, a source of sanguinary pride.

Buzkashi was integral to the formation of alliances in warfare. It provided an opportunity for pan-tribal communication at many different levels It challenged the virility and equestrian skills of every participant. It validated the leadership of competing champions. And it allowed the nomads to assess the spirit and horsemanship of other groups competing. Success in hosting the games brought the chieftain sponsor respect at home, renown abroad, and ready partners in warring. Failure to participate boldly in the contest earned only scorn and hostility. From the ritual slaughter of the calf and bloody carcass sprang new links of trade and friendship, new alliances for war.

A sport akin to buzkashi, polo is also of steppe origins. Possibly the most ancient reference to the game occurs in the Persian Shahnameh (Book of Kings), where it is recounted that in the legendary contest against Turanian invaders from the steppes the famed Iranian prince Siyavush galloped so fast and hit so hard that the ball in an instant flew face to face with the moon. The enlightened Sasanian Shah Khosrau (531-579) was an also accomplished polo player, as was his beautiful consort Shirin. The poet Nezami wove an exquisite love story around the two monarchs’ polo matches with their courtiers. At a polo ground alongside the Silk Road, a stone tablet was inscribed “Let other people play at other things, the king of games is still the game of kings.” From Persia polo spread to Byzantium, Arabia, Tibet, China, and Japan, where the polo stick featured prominently in the heraldry of those cultures. During the Tang dynasty, polo was practiced at the Chinese court by both men (some bearded) and women at a special polo field within the palace.

The game was also played by Turks. As indicated in the furusiyya manuals of drill and instruction, military training for the Kipchak Mamluk slave corps of Egypt was grueling., Polo, however was considered the most strenuous practice, in which horse and rider together would prepare their hearts for the perils of battle, turning, defending, charging, struggling with the adversary, snatching the ball, racing free – exercises to hone the daring and dexterity of the successful warrior in combat. The Mamluk general Baybars, who defeated the Mongols at the battle of Ayn Jalu in 1260, built two superb hippodromes in Cairo expressly to accommodate these maneuvers. The Turkic conqueror Tamerlane would of course play polo with the decapitated heads of prisoners. His descendant Akbar(1556-1605) who extended the Mughal empire east to the Bay of Bengal and south to the Deccan, was a great polo enthusiast, playing matches at night under torchlight.

Akbar’s exploits were rivaled by the Safavid Shah Abbas, who transformed Isfahan into a architectural wonderland, central to which stood the hippodrome, illuminated at night by 50,000 lamps. The towering royal tribune provided a grandstand from which royalty and guests reviewed troop parades and polo matches. When the Shah scored, trumpeters sounded the salute. It was in Assam that the British first played polo. British tea planters learned the game from the Manipuris and formed the Silchar polo club in 1859. The game with eight players to a team had almost no rules but was soon adopted by British cavalry units in India, whence it spread to every corner of the British empire – and beyond. In Australia, it was even played in remote desert locales on donkeys. Today, the sport is dominated internationally by the Argentines who, proud of their hard-riding gaucho heritage, hold a virtual monopoly of top ranked active 10-goal players.

Next week: The Mongol Horse in War and Peace >>

Reference: Kalter, Johannes 1997 Aspects of Equestrian Culture. In Heirs to the Silk Road: Uzbekistan. Johannes Kalter and Margareta Pavaloi, eds. Pp. 168–187. London; New York: Thames and Hudson.

Latest Comments

Have your say!