World War II trauma and disruption shaped modern Southeast Asia. Japanese occupation cost the lives of 4.5 million Southeast Asian civilians in the region’s countries of Burma, Malaya, Thailand, Indonesia, Indochina and the Philippines. GDP in Southeast Asia spiralled downwards, bottoming out at half or less of its pre-war levels by 1945.

Before the December 1941 extension of World War II to the Pacific War following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan had already determined to send no goods or medicines to Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia, highly specialized in the export of primary commodities, was too weakly industrialized to manufacture sufficient of nearly all basic goods, even cloth and thread. Southeast Asians fashioned garments from gunny sacks, normally used to carry rice and sugar. Veins of pineapple plant leaves substituted for sewing thread.

Famine was the greatest killer. Between 1944 and 1945, a million people starved to death in Vietnam’s north around Hanoi. Over two million perished in Java. By 1944, almost all of Southeast Asia’s 145 million population was malnourished, often acutely.

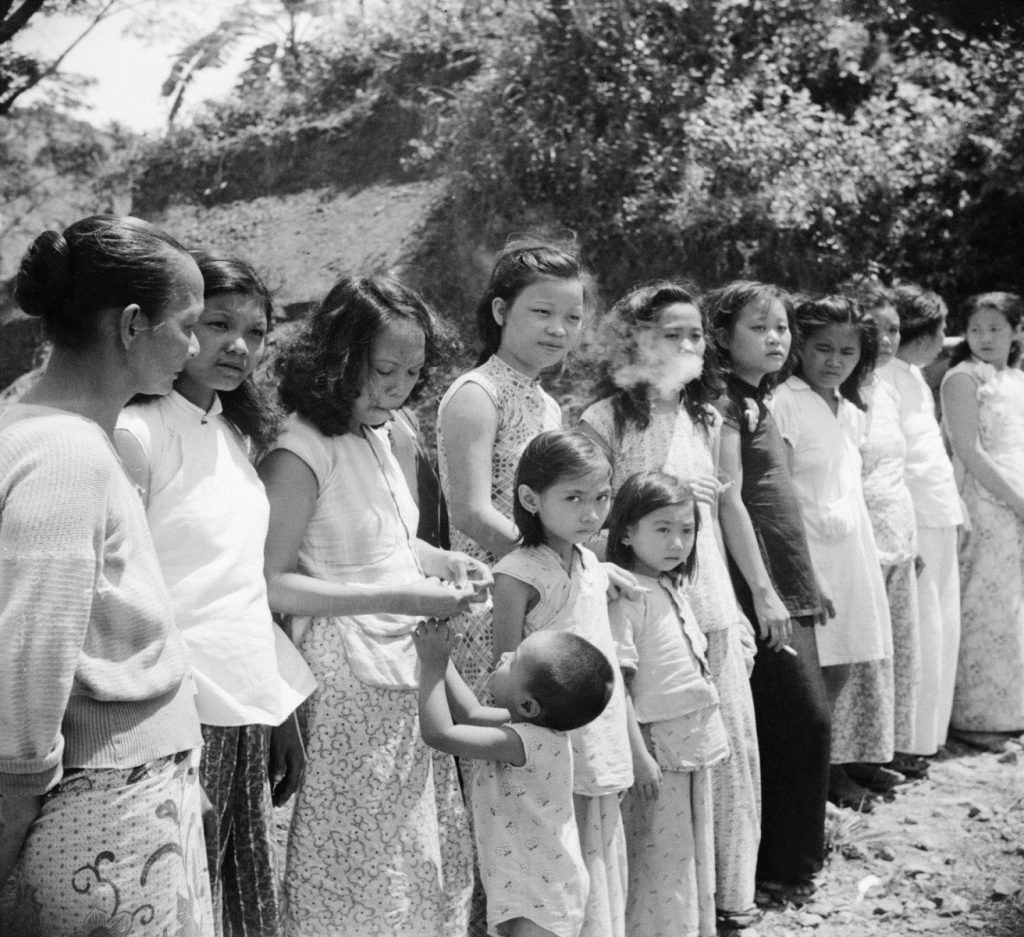

Forced labour and comfort women add to the occupation’s uncomfortable legacies. Notorious is the Thailand-Burma Railway, constructed across impossible terrain and malarial jungle by British and Commonwealth POWs and Southeast Asians. A combined total of 86,000 died, 573 people per mile of railway built. Some 20,000 Southeast Asian women were forced into the Army’s and Navy’s comfort stations. The Singapore Chinese Girls’ School became a comfort station, as, early on, did, the Raffles Hotel.

Black markets proliferated. Even the Japanese Army turned to Southeast Asians peddling stolen or looted goods. Southeast Asians, needing money for food, sold family heirlooms and jewellery to black market traders. Some of these men became fabulously wealthy, Manila’s ‘buy and sell’ merchants, Malaya’s ‘mushroom millionaires’ and Rangoon’s New Order Brokers.

Prostitution and gambling soon became rife. Coffee shops and restaurants advertised for young women as ‘waitresses’. Some women had no way except casual prostitution to feed their families. Guerrillas, especially in Malaya the Philippines, offered a counterweight to Japan’s army in the countryside. Cities, however, under tight control, remained quiet. Brutal Japanese torture was instrumental in this.

Political and economic legacies of the war were far reaching. There was ‘no return to the old peaceful, stable, free-and-easy Singapore’, Lee Kuan Yew remarked of an area of Southeast Asia less troubled than most. Every country except Thailand experienced civil war or revolution. Ho Chi Minh in Viet Nam, Sihanouk in Cambodia, Sukarno in Indonesia and Ne Win in Burma were World War II creations. These men and their direct successors went on to rule Southeast Asia for decades.

The sudden end to the war after the two American atomic bombs left a vacuum. Vietnam’s famine was fundamental to the rise of Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh. With at most 900 men and many fewer rifles, the Viet Minh took control of Hanoi on the night of 19 August 1945. Economically, Malaya and Thailand alone recouped relatively rapidly. The Philippines recovered to its 1938 level of GDP per capita only in 1957; Vietnam reached this mark in 1962 but then slid backwards. Indonesia fully matched 1938 GDP per capita in 1961, while Burma finally regained 1938 income 40 years later, in 1978.

Latest Comments

Have your say!