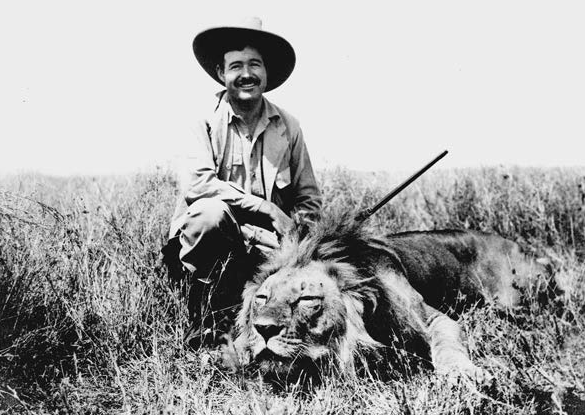

The fifth volume of The Letters of Ernest Hemingway spans January 1932 through May 1934. With the critical and commercial success of his 1929 novel A Farewell to Arms, Hemingway had achieved international renown and entered his prime. During this period he completed and published Death in the Afternoon (1932), his nonfiction treatise on bullfighting and writing, and the short-story collection Winner Take Nothing (1933), featuring such classics as “A Clean Well-Lighted Place” and “Fathers and Sons.” When not actively writing, he was most often fishing or hunting in the company of family and friends, crisscrossing the United States from Key West, Florida, to Piggott, Arkansas, to the wilds of Wyoming and Montana; pursuing his new passion for big game fishing in the Gulf Stream off the coast of Cuba; and embarking on a long-anticipated safari in British East Africa. He also began contributing articles to the newly established men’s magazine Esquire in the form of “Letters” chronicling his adventures for a wide popular readership. Upon his return from Africa in April 1934, he purchased his beloved boat Pilar–today enshrined on the grounds of Finca Vigía, his longtime Cuban home, now a national museum.

Volume 5 includes 393 items of correspondence directed to 100 recipients. Among his most frequent correspondents are the legendary Scribner’s editor Maxwell Perkins, Esquire editor Arnold Gingrich, and fellow writers Archibald MacLeish, John Dos Passos, and Ezra Pound. The letters afford fresh insight into his literary friendships. Hemingway expressed admiration and praise for MacLeish’s Pulitzer-prize winning poem Conquistador and for the innovative techniques of Dos Passos’s latest book, 1919, the second in his U.S.A. trilogy. He took Dos Passos’s literary advice to heart, cutting sections of Death in the Afternoon after Dos Passos read it in typescript while visiting Key West. Of his work-in-progress, Hemingway wrote to Perkins, “It’s a good book Max and you know what Dos says— That the performance of the book should be judged by the author by the quality of the stuff he is able to cut—”

In a letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway detailed what he saw as fatal flaws in his old friend’s new novel, Tender is the Night (1934), his first in nine years. In letters to mutual friends, Hemingway lamented what had become of Scott, whose wife, Zelda, was under treatment for mental illness while he battled his own demons of drink and despair.

Hemingway’s letters also afford intimate views of his family relationships. They express his love for his wife, Pauline, and pride in his three young sons; his vehement disapproval of his youngest sister’s marriage, which would leave the two permanently estranged; his exasperation with his mother’s “noble moral tone” and perceived ingratitude for the Trust Fund he had established for her after his father’s 1928 suicide; and his easy, good-humored affection for Pauline’s mother. While vacationing in Wyoming, he had driven Pauline 372 miles round trip to take Holy Communion, breaking the entire bottom out of the car on a rock on the way back: “So if she is ever canonized that feat should be mentioned,” he quipped to his mother-in-law.

Increasingly, Hemingway had to contend with the consequences of celebrity. He quarreled with Paramount Pictures over the 1932 movie adaptation of A Farewell to Arms (starring Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes), for which the studio had filmed an alternate “happy ending” in which the heroine does not die in childbirth. When the leftist critic Max Eastman published a review of Death in the Afternoon titled “Bull in the Afternoon” (New Republic, June 1933) charging that Hemingway wore “false hair” on his chest, Hemingway was enraged. In letters to an array of recipients, he vowed to break Eastman’s jaw if he ever encountered him in person. (In 1937 the two would meet by chance in Max Perkins’s office, with Hemingway hitting Eastman in the face with a book and Perkins breaking up the fight.)

Hemingway viewed letter writing as a distraction from his “real” writing. To fellow writer Eric Knight, he apologized for being a lax correspondent: “Cant write and write letters. Wish to Christ I could.” Yet even if he did not take them seriously, Hemingway’s letters hold enormous interest and value as a chronicle of his life and times in the continuous present tense.

Image credits: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Latest Comments

Have your say!