This case marks the first time the Supreme Court will address the issue of same-sex marriage in America. Here at Cambridge University Press, we rounded up six of our experts on the issue for a virtual roundtable discussion about the case and its impact.

This case marks the first time the Supreme Court will address the issue of same-sex marriage in America. Here at Cambridge University Press, we rounded up six of our experts on the issue for a virtual roundtable discussion about the case and its impact.

The Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution: “[N]or shall any State…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Proposition 8 (Article I, Section 7.5 of the California Constitution): “Only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California.”

Moderator: The question presented in Hollingsworth v. Perry is “whether the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the State of California from defining marriage as the union of a man and a woman.” What does it mean for our country that the same-sex marriage controversy is finally being addressed by the Supreme Court?

Daniel R. Pinello: The same-sex marriage controversy has been a long time coming. Twenty years ago, the Hawaii Supreme Court was the first high tribunal to suggest there might be a constitutionally protected right of lesbian and gay couples to marry. Ten years ago, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court was the first to say unequivocally that indeed there was such a right in the Bay State. All of this judicial activity, however, prompted a significant backlash. Today, at least 30 states have amended their constitutions to limit marriage to the union of one man and one woman. So there’s a great deal riding on the Supreme Court’s decision this year.

Shannon Gilreath: I think this is actually a complicated question. When the Court decided Loving v. Virginia, striking down the country’s remaining antimiscegenation laws, it invoked an explicitly anti-supremacist rationale. But Loving is increasingly irrelevant to the Court’s modern equality jurisprudence. Subsequent decisions on race have been acutely anti-identitarian, pursuing a “color blindness” norm. Decisions have dismantled affirmative action, for example, under an “equality” theory of color blindness. This shift in race jurisprudence has made the 14th Amendment into a guarantor of majoritarian power. Lawrence v. Texas, striking down anti-sodomy laws, likewise pursued a “blindness” rationale, assimilating the gay litigants into an overwhelming “like-straight” theory. A decision on gay marriage following this kind of formal equality theory is good only as a short-term victory. I think it’s time we started thinking long-term.

Kathleen E. Hull: It seems that this case represents a fork in the road in terms of legal treatment of same-sex relationships in the U.S. If the Court rules California’s ban on same-sex marriage unconstitutional, all of the other state-level bans will most likely be challenged and eventually overturned, clearing the path toward legal same-sex marriage across the nation. But if the Court upholds the California ban, the status quo will reign for the foreseeable future, with the large majority of states continuing to prohibit same-sex marriage by statute or amendment. A few more states will likely add marriage recognition as time goes on, but the nation will remain deeply divided in its legal treatment of same-sex couples.

Kathleen E. Hull: It seems that this case represents a fork in the road in terms of legal treatment of same-sex relationships in the U.S. If the Court rules California’s ban on same-sex marriage unconstitutional, all of the other state-level bans will most likely be challenged and eventually overturned, clearing the path toward legal same-sex marriage across the nation. But if the Court upholds the California ban, the status quo will reign for the foreseeable future, with the large majority of states continuing to prohibit same-sex marriage by statute or amendment. A few more states will likely add marriage recognition as time goes on, but the nation will remain deeply divided in its legal treatment of same-sex couples.

Marsha Garrison: Equality is an evolving concept. At the time Jefferson declared that all men are created equal, popular notions of equality were not incompatible with the disenfranchisement of women and even slavery. We now take it for granted that equality disallows laws that explicitly discriminate based on characteristics such as race and gender. Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, equality has expanded to require affirmative action to remedy past wrongs and to forbid facially neutral laws that disproportionately harm a particular group. A victory for the plaintiffs in Perry would build on these developments: it might recognize sexual orientation as a characteristic, like race and gender, that should not determine rights; it might require the state to alter the definition of marriage to avoid that definition’s disproportionate negative impact on same-sex couples.

Michael J. Perry: It is possible—possible—that SCOTUS will rule that the Fourteenth Amendment requires states to provide civil unions for same-sex couples—even civil unions that are fully the equivalent of civil marriage in terms of the attendant benefits and burdens—but that the Amendment does not require states to call such civil unions “marriage.” Under such a ruling, California’s Prop 8 would stand. Nonetheless, the ruling would be anathema to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and others who oppose civil unions for same-sex couples no less vigorously than they oppose calling such unions “marriage.”

Kathleen E. Hull: That’s a good point. I have been assuming that the justices that are inclined to find a violation of the 14th amendment will take the position that only “marriage” fulfills the guarantee of equal protection, but maybe not.

Equality is an evolving concept. At the time Jefferson declared that all men are created equal, popular notions of equality were not incompatible with the disenfranchisement of women and even slavery.

Evan Gerstmann: We don’t know what it means yet. The Court might only be interested in technical issues such as standing. Or the Court might be interested in process issues such as whether referendums and initiatives can take revoke rights that state courts have found fundamental under state constitutions. Nonetheless, the fact that Court is hearing this argument at all, along with the favorable state votes on same-sex marriage in the 2012 election, and President Obama’s evolution on gay and lesbian equality issues represents enormous progress.

Marsha Garrison: Well put! But there’s the risk that a strong decision against same-sex marriage could set back legislative progress, just as the Glucksberg decision (1997) set back legislative activity on physician-assisted suicide. The $64 question is whether the plaintiffs’ lawyers have accurately judged the mood of the Court.

Daniel R. Pinello: Twenty state constitutions prohibit recognition of all forms of relationship rights —marriage, civil unions, domestic partnerships, reciprocal benefits, etc. —for same-sex couples. Dubbed “Super-DOMAs [Defense of Marriage Act],” these measures aspire to insure that lesbian and gay pairs can be nothing other than legal strangers to one another. Super-DOMAs seek to restrict the word “marriage” and all of its attributes to heterosexual couples, which exclusivity creates serious problems for their homosexual counterparts. In 2008, for example, the Michigan Supreme Court interpreted the Michigan Super-DOMA to require the denial of health insurance and other employer-provided benefits to the same-sex partners of all state employees.

Michael J. Perry: I don’t understand the point about setting back legislative progress. A ruling that states are not constitutionally required to do something—e.g., decriminalize physician-assisted suicide or admit same-sex couples to civil marriage—leaves states constitutionally free to do what they are not constitutionally required to do. That for a long time—much too long! —states were not constitutionally required to abandon antimiscegentation laws did not keep a growing number of states from doing just that. Indeed, it may be that sufficiently widespread legislative progress on an issue provides SCOTUS with the cover it sometimes seems to think it needs, or in any event the cover it sometimes seems to want, before ruling that all states are constitutionally required to do what many states have chosen to do.

Marsha Garrison: A strongly negative outcome in SCOTUS can subtly shift public opinion and legislative trends; it’s not a necessary outcome, but it is certainly a possible outcome. An ill-timed lawsuit (like Glucksberg) thus can retard legislative progress on a particular issue. I would guess that the plaintiffs’ lawyers have decided that this is a risk worth taking because most of the legislative activity on same-sex marriage that’s plausible over the short term has already happened. In most of the states that have not legislatively or constitutionally banned same-sex marriage, legislatures have already sanctioned it. And in the 30 or so states that do constitutionally ban same-sex marriage, it could well be decades before these prohibitions are undone if SCOTUS does not declare them unconstitutional. The question still remains as to whether this is the right moment. Once SCOTUS has spoken, it is not likely to revisit the issue soon. It was 17 years before SCOTUS reversed its decision in Bowers v. Hardwick, upholding criminal sodomy prohibitions, and declared such laws unconstitutional.

Marsha Garrison: A strongly negative outcome in SCOTUS can subtly shift public opinion and legislative trends; it’s not a necessary outcome, but it is certainly a possible outcome. An ill-timed lawsuit (like Glucksberg) thus can retard legislative progress on a particular issue. I would guess that the plaintiffs’ lawyers have decided that this is a risk worth taking because most of the legislative activity on same-sex marriage that’s plausible over the short term has already happened. In most of the states that have not legislatively or constitutionally banned same-sex marriage, legislatures have already sanctioned it. And in the 30 or so states that do constitutionally ban same-sex marriage, it could well be decades before these prohibitions are undone if SCOTUS does not declare them unconstitutional. The question still remains as to whether this is the right moment. Once SCOTUS has spoken, it is not likely to revisit the issue soon. It was 17 years before SCOTUS reversed its decision in Bowers v. Hardwick, upholding criminal sodomy prohibitions, and declared such laws unconstitutional.

Daniel R. Pinello: The cause of gay civil rights has advanced recently with breath-taking speed. Congress repealed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in 2010. Then New York authorized same-sex marriage in the third most populous state. Voters in Maine, Maryland, and Washington approved of marriage equality last year, while Minnesotans defeated a constitutional amendment to ban it — the first plebiscites ever to favor the relationships rights of gay and lesbian pairs. Moreover, legislative leaders in Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, and Rhode Island are promoting marriage equality this year. Couldn’t conservatives now make a compelling federalism argument to swing justices that SCOTUS ought not to intervene when such political dynamics are in play?

Evan Gerstmann: I agree that one of the conservatives’ best argument to the Court is that they should let the democratic process play out. It would be very frustrating if the Court ruled against marriage equality on this basis since there was no absolutely no reason for the Court to take this case if that is how they see it. The Ninth Circuit took great pains to use reasoning that only applies to California. If the Court truly wants to let the democratic process play out, all they had to do was deny cert.

Daniel R. Pinello: How very true, Evan. I so hoped last fall that SCOTUS would accept just the DOMA challenge (the Windsor case) for this term and leave the Ninth Circuit’s Prop 8 resolution undisturbed. Now, with each additional political advance in marriage equality (such as the state senate’s passage of a SSM bill in Illinois a few days ago), I lie awake at night worrying that Perry will result in another Hardwick setback.

Shannon Gilreath: I completely agree with you on this point. Whatever else may come of it, I think the Perry litigation shows a disturbing lack of solidarity.

Moderator: The Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution decrees that “nor shall any State…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” From this constitutional standpoint, should a California state ban on same-sex marriage hold up?

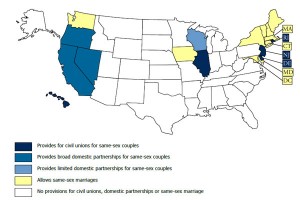

The National Conference of State Legislature’s map of states where marriage rights and civil unions are extended to same-sex couples.

Daniel R. Pinello: For about a decade, California has offered same-sex couples a comprehensive, legislatively created scheme of domestic partnerships that effectively provides them virtually all the tangible rights, benefits, and responsibilities of civil marriage. What the California plan does not supply lesbian and gay pairs and their families is the perceived dignitary value of marriage. The 14th Amendment question for SCOTUS in Perry boils down to the same kind of separate-but-equal analysis that the Court faced in its 20th Century race-relations decisions. Do full domestic partnerships afford California same-sex couples “the equal protection of the laws”? Many of those pairs certainly don’t think so. An interesting empirical question for SCOTUS here is: How many of the couples receiving California domestic partnerships over the last ten years have been opposite-sex? In other words, when pairs may freely choose between civil marriage and domestic partnerships, with what frequencies do they select the former and the latter?

Marsha Garrison: The California law doesn’t permit that sort of empirical comparison as it makes domestic partnership available to heterosexual couples only when one partner is 62 or older. But in France, which offers something like a domestic partnership (pacte civile) to both heterosexual and same-sex couples, 94% of couples becoming pacse (as the French put it), were opposite-sex in 2012. Moreover, marriage rates in France continue to decline while pacte civile rates continue to increase; at least two-fifths of French heterosexual couples entering into some kind of union are become pacse. France is not the United States, of course, but there is some irony in the fact that the debate over same-sex marriage is taking place at a time when heterosexual marriage is in decline virtually everywhere. In Perry, SCOTUS could duck the head-on equal protection question by adopting the 9th circuit’s reasoning, which relies on the fact that California offered same-sex marriage and then took it back. This very narrow equal protection analysis would not apply in most other states.

Evan Gerstmann: I strongly believe that the ban on same-sex marriage violates the equal protection clause. No one can articulate a strong reason for the ban so it can only pass the most deferential version of the rational basis test and would fail the even slightly heightened test the Court has applied in various cases. And no one has articulated a reason that Same-sex couples aren’t protected by the fundamental right to marry. Since felons in prison and “dead beat dads” who aren’t supporting their children from previous marriages are explicitly protected by the right to marry, that right can hardly be limited to traditional marriage. I think the reason this issue has gained so much traction is that people are beginning to see that same-sex marriage harms no one and represents government interference with one of the most personal of all decisions.

Daniel R. Pinello: I was unaware that California domestic partnerships were unavailable to all opposite-sex couples. The California legislature apparently stacked the empirical deck. Perhaps it didn’t want the comparison to be made, believing that such scrutiny would put the lie to the political claim of presumptive equality. Have any heterosexual couples (where both are under the age of 62) sued for domestic partnerships in California? That would be a fascinating equal-protection claim. If there are indeed no heterosexuals storming the barricades for domestic partnerships, isn’t the absence of such litigation at least some indication that California opposite-sex couples don’t value domestic partnerships as much as civil marriage?

Marsha Garrison: What an interesting question! I can’t think of any lawsuits on the unique (as far as I know) and curious 62-&-older requirement in California.

Shannon Gilreath: The answer to the underlying question, which is whether the 14th amendment forbids state bans on same-sex marriage, is an emphatic “yes.” As a question of doctrine, as Evan points out, it isn’t even a difficult question. Far more interesting is the question of leadership that seems to be elided in most of the mainstream discussion. A number of the responses here hint at it. What about domestic partnerships and civil unions? Are they really so inferior an undesirable. Of course, individuals want what they want, and generally they want those things for largely unexamined reasons. Structurally, the issue is more complicated. I think that gay people have missed a great opportunity here to lead—to make progress that is real and concrete. Instead of insisting on a strategy that dovetails perfectly with compulsory marriage, why couldn’t we have supported alternative structures on our own terms? Why couldn’t we have said, “We want something better than what your inherently heterosexual institution allows”? To my mind, a substantive equality decision is one that allows the minority to set the rules and shape the values. Even in the unlikely event that the Court answers the marriage question is the way the doctrine seems to demand, there are still only the old values here. An uncritical (and unexamined) movement isn’t much of a movement.

Even in the unlikely event that the Court answers the marriage question is the way the doctrine seems to demand, there are still only the old values here. An uncritical (and unexamined) movement isn’t much of a movement.

Daniel R. Pinello: Why should the LGBT minority be any less middle class than everyone else? I’ve conducted in-depth interviews with 170 same-sex couples in six Super-DOMA states (Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Ohio, Texas, and Wisconsin) for a new book. I asked them questions such as “Have you had a ceremony to celebrate your relationship?” and “Are you interested in getting married to each other?” The overwhelming majority indicated that marriage is their gold standard for relationship recognition. They aspire to emulate their parents, other relatives, and friends who’ve been married. Civil unions and domestic partnerships are acceptable in a pinch. But none of them said anything like “We want to create a new, unique, innovative institution that will inspire others to follow our trail-blazing example.”

Kathleen E. Hull: The policy goal of marriage seems to align with what many “average” same-sex couples say they want, and indeed in some of my research I have had gay and lesbian people express shock (and occasionally outrage) at the idea that any sexual minority individual would oppose or question the marriage goal. But of course marriage is a fraught institution, carrying a lot of baggage in terms of oppressive gender relations and social control of sexuality. So I don’t think the fact that many or most same-sex couples today report the desire for marriage means we should view that desire uncritically or refrain from speculating on whether there was a lost opportunity here, in terms of moving the law (and society) toward a more expansive and inclusive model of family and relationship recognition. And there is certainly an irony in the fact that gays and lesbians are so eager to gain access to marriage at the very historical moment when straight people are increasingly questioning the institution’s value and viewing it as an optional lifestyle choice rather than an inevitable life course milestone.

Evan Gerstmann: To my mind the issue isn’t whether marriage is a positive or negative institution any more than getting rid of DADT [Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell] is about whether the military is a positive or negative institution. No group of people can be equal and free citizens without access to basic civil institutions such as military service or marriage. Marriage equality no more requires a re-examination of marriage than getting rid of DADT requires a re-examination of American militarism. Of course critical examination of gender stereotypes and militarism are important goals, but equality for all citizens is a separate issue and need not be linked to or subsequent to that.

Daniel R. Pinello: My current project on Super-DOMA states has many objectives. Yet one research inquiry was personal since, a long time ago, I lived in Louisiana and Ohio, which would later adopt these constitutional amendments. The question is: Why don’t same-sex couples leave these places that make them pariahs and go somewhere that welcomes their relationships? After all, the remedy for a complete lack of familial rights is sometimes as simple as crossing a border, such as going from Virginia to Maryland. So why don’t more lesbian and gay pairs just move (as I had, twice)? Interviewing the 170 couples, I learned that most of them regularly struggle with the migration option. Yet they face challenges involving ties to home, job, family, and community that are daunting and profound — and therefore immobilizing. I admit now that I did the couples no service by criticizing their behavior from afar. Others who also implicitly judge them for not meeting unspecified utopian ideals should consider my example.

Michael J. Perry: I argue in my new book—Human Rights in the Constitutional Law of the United States—which Cambridge will publish later this year, that as a federal constitutional matter, the better constitutional argument for requiring states to admit same-sex couples to civil marriage is based not on the right to moral equality—which is internationally recognized as a human right and appears in U.S. constitutional law as the right to equal protection—but on the right to religious and moral freedom—which is also internationally recognized as a human right and a variant of which has emerged in U.S. constitutional law as the right of privacy. It takes me a couple of chapters of my book to explain why (in my judgment) this is so. I submit this post as a promissory note.

Daniel R. Pinello: Can Cambridge send nine advance copies to the Supreme Court soon? We need all the constitutional ammo we can muster!

Moderator: Proposition 8 was a voter initiative in California. Do “we the people” have the right to decide who someone can or cannot marry? From an ethical standpoint, should we?

Evan Gerstmann: “The People” most definitely do NOT have the right to decide who can marry. We have majority rule for most decisions—-tax rates, spending priorities, the speed limit and so forth. But there are certain areas of individual autonomy such as what neighborhood we live in, what religion we practice and where we send our children to school that cannot be subject to majority rule. Whom we marry is one of those areas of individual autonomy. Society can impose limitations of course—one can’t marry a five year old—but those limitations can’t be imposed merely because the majority wants them. They must be based on public policy concerns that can withstand heightened judicial scrutiny.

Shannon Gilreath: I think the answer is a clear, “yes.” It seems entirely ethical for the state to proscribe certain marriages that entail force and victimization, including marriages involving minors, but also other types of relationships; for example, incestuous relationships under certain conditions, and others in which a capacity for meaningful consent is questionable.

Marsha Garrison: I see an interesting debate here! But I think disagreement hinges on question interpretation. First, the very point of a right is that the majority — elected by voters or voters themselves — can’t take it away. But rights are rarely absolute; they may be limited when the restrictions are reasonable and serve important legislative goals. Freedom of speech is guaranteed by the Constitution but today, we all agree that you can restrict the right to yell “Fire!” in a crowded movie theatre. We don’t agree, for example, whether speech rights disallow legislative limits on campaign donations and whether corporations enjoy the same speech rights as private individuals. Access to marriage is a right, and we all agree that a legislature (or voters) could not deny marriage to, say, all persons who have ever divorced. We agree that the state can limit marriage to adults. We haven’t thought much about restrictions on marriage to cousins and adoptive relatives (which many states still have) because it’s so easy to evade these limitations by going to another state that no one has challenged them. The same-sex marriage issue is an easy or hard case depending on what we mean by marriage. If marriage is an important status, then it must be freely available to all citizens. If it is a cultural institution limited to heterosexual couples (as those opposing same-sex marriage argue), then legislatures may maintain its historic definition. Personally, I think the best analogy is to rules that previously granted non-marital children fewer rights than marital children. These were struck down during the 60s. They also had a very long (and virtually worldwide) cultural history. Times change; cultural institutions and our conception of rights must change with them.

Marsha Garrison: I see an interesting debate here! But I think disagreement hinges on question interpretation. First, the very point of a right is that the majority — elected by voters or voters themselves — can’t take it away. But rights are rarely absolute; they may be limited when the restrictions are reasonable and serve important legislative goals. Freedom of speech is guaranteed by the Constitution but today, we all agree that you can restrict the right to yell “Fire!” in a crowded movie theatre. We don’t agree, for example, whether speech rights disallow legislative limits on campaign donations and whether corporations enjoy the same speech rights as private individuals. Access to marriage is a right, and we all agree that a legislature (or voters) could not deny marriage to, say, all persons who have ever divorced. We agree that the state can limit marriage to adults. We haven’t thought much about restrictions on marriage to cousins and adoptive relatives (which many states still have) because it’s so easy to evade these limitations by going to another state that no one has challenged them. The same-sex marriage issue is an easy or hard case depending on what we mean by marriage. If marriage is an important status, then it must be freely available to all citizens. If it is a cultural institution limited to heterosexual couples (as those opposing same-sex marriage argue), then legislatures may maintain its historic definition. Personally, I think the best analogy is to rules that previously granted non-marital children fewer rights than marital children. These were struck down during the 60s. They also had a very long (and virtually worldwide) cultural history. Times change; cultural institutions and our conception of rights must change with them.

Michael J. Perry: And then there are those who are now arguing, in effect, that “marriage” is a “natural kind”—so to speak; not their words—and that a union between two persons of the same sex is no more a “marriage”—can no more be a “marriage”—than, say, lead can be gold. The most prominent and influential version of the argument: What Is Marriage?: Man and Woman: A Defense, by Sherif Girgis, Ryan T. Anderson, and Robert P. George.

Moderator: What are some of the concerns that prompt ProtectMarriage.com to argue that States should be able to define marriage in particular gendered terms?

Michael J. Perry: The particular concern that prompts “ProtectMarriage.com to argue that States should be able to define marriage in particular gendered terms” is the end of Civilization as we have known it. Sorry, couldn’t resist that.

Marsha Garrison: I just checked ProtectMarriage.com’s website and, interestingly, it reveals no names or affiliations. But it is part of a network of organizations that have supported policy initiatives favoring traditional marriage. Many of these organizations and their supporters have religious values that favor traditional marriage. They are also, well, traditionalists! The explicit argument is that marriage is a cultural institution indelibly linked with child-bearing and rearing; to tamper with the definition risks grave harm to these core functions and thus to society. But its context is conservatism in family values and a traditional religious outlook.

Shannon Gilreath: Michael and Marsha are right, of course, that it is all about “civilization” and “values.” It makes the gay conservative argument that marriage is what we (gays) need to civilize us all the more interesting, particularly when one looks around at the world today and marvels at what “civilization” according to straight values has wrought.

Daniel R. Pinello: As a political scientist, I note that conservatives usually favor state action over federal preemption. In theory, federalism (the separation of powers between a national government and sub-national units like states) facilitates states being laboratories of innovation. Moreover, what works for New York may not fit Idaho well. Under federalism, then, states are free to determine what functions best for each, without the national government establishing one-size-fits-all approaches. In short, ProtectMarriage.com, inter alia, is making a pitch to center-right justices like Anthony Kennedy and John Roberts for the Supreme Court—a national institution, after all—to let the states work out the marriage issue for themselves.

Daniel R. Pinello: The media recently covered a friend-of-the-court brief filed with the Supreme Court in the Perry case. A front-page story in the New York Times began “Dozens of prominent Republicans have signed a legal brief . . . ,” while the headline at politico.com was “More than 80 Republican leaders sign pro-gay marriage brief.” Yet only four of the signatories are current officeholders: two members of Congress, a New Hampshire state senator, and a Wyoming state representative. Just 12 others were ever elected to public office. Since the prospective pool of current and former state and federal GOP officials numbers in the thousands, the brief-signing group is truly minuscule. Indeed, rather than demonstrating that marriage equality has significant bipartisan support, the document evidences how unified the Republican Party is against same-sex marriage—which in turn reinforces ProtectMarriage.com’s federalism argument to the justices.

Moderator: With a few prominent Republicans like Meg Whitman and Jon Hunstman actually reversing their positions on the issue to sign a brief in support of same-sex marriage in this case, how might a nascent or suggested political shift on the issue affect legal considerations of the petitioners’ concerns? Does the brief suggest that the debate on same-sex marriage is headed in a new direction regardless of the court’s ruling?

“The party of Lincoln should stand with our best tradition of equality and support full civil marriage for all Americans.”—Jon Hunstman

Michael J. Perry: Jon Huntsman’s statement in The American Conservative last week—you can Google it—was quite honest. Huntsman said that admitting same-sex couples to civil marriage is not only the right thing to do, but that once that issue—and presumably some other “social” issues—are off the political agenda, Republicans will have been liberated to press the issues many Republicans care most about, which are economic, not “social.” The Koch Brothers are major contributors to “gays rights” causes, including Marriage Equality. I have no doubt that the Koch Brothers would dearly love to free the Republican Party from the “social” issues now (in their view) holding it back. Of course, other influential Republicans—not least, Robby George of Princeton—care more about the “social” issues: same-sex marriage, abortion. So the Republican Party is, at this time, extremely divided; the civil war, as someone said, has begun.

Marsha Garrison: Jon Huntsman and the Koch brothers may well want to “free” American Republicans from social issues, but the Republican Party has courted evangelical and “traditional social values” voters—who are in no mood for freedom—for a long while, and they don’t really have any place else to go. Keep in mind that about half of Republican primary voters in 2012 self-identified as evangelical, and the percentage is even higher in some states. These voters and the organizations to which they belong are going to want to keep the Republican Party tied to their social agenda. I’m not sure there are enough Republicans who share Huntsman’s values—or who are willing to go public with Huntsman’s values given the likely Republican electorate—to generate any real change or even a real Republican Civil War.

Michael J. Perry: If what Marsha predicts comes true—time will tell—then we will have only one political party capable of winning a national election—assuming that that party does not suffer any disabling self-inflicted wounds.

Daniel R. Pinello: As events in recent years (highlighted in earlier messages) document, the political debate surrounding same-sex marriage has already decisively shifted at the national level. If the Supreme Court strikes down the federal DOMA in the Windsor case—a reasonable assumption—the principal challenge for marriage-equality advocates will be the vitality of state Mini- and Super-DOMAs. If the Perry Court does not announce a federal right of gay couples to marry, then the state amendments will have to be repealed in the same way in which they were added: with statewide popular votes. That will not be easy, because even the modest majorities favoring SSM achieved last November in Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, and Washington will not be replicated soon in places like Georgia, Michigan, Ohio, and Texas. Just last May, for instance, 61 percent of primary voters in North Carolina approved its Super-DOMA. Thus, without decisive Supreme Court action now, there will be no “new direction” on SSM in many states for at least a decade or more. Indeed, my bet on the timing of such DOMA repeals is when the business communities in the respective states reach overwhelming consensus that they can no longer attract and retain skilled workers because of these amendments.

Kathleen E. Hull: I agree with Dan, that this brief by Republicans is more reflective of a political shift on same-sex marriage that was already underway, rather than signaling the start of a shift. I don’t think any of us has directly addressed the first part of Rachel’s question, though, which is whether a brief like this is likely to have any impact on the “legal considertions of the petitioners’ concerns.” I take this to mean: could this brief possibly sway any of the Supreme Court justices? I don’t feel qualified to answer this myself, and I don’t know if it is even answerable, but if anyone has knowledge about the potential of amicus briefs to influence justices, I would be interested to hear their take on this. My suspicion is that, if it has any impact at all (which is dubious), it would be in providing cover for moderate justices like Kennedy (or maybe even Roberts?) to rule in favor of the plaintiffs. And yes, I realize that in general it is probably not accurate to characterize Roberts as a moderate(!), but he did uphold the constitutionality of the health reform law, which at least signals his willingness to depart from “party-line” conservatism on some issues.

Michael J. Perry: I’ve been teaching and writing about Con Law for thirty-eight years. For what it’s worth, I’m concur in Kathy’s judgment on this with respect to Kennedy. (Her “providing cover” judgment.) However, I would be truly shocked if Roberts were to vote in favor of the constitutional challenges, other than the federalism challenge (not the equal protection/due process challenge) to DOMA, which, for all I know, he might support.

Evan Gerstmann: The most significant recent example I know of where an amicus had a big impact on a case was the military brief in support of affirmative action in Grutter. My understanding was that the impact came not from the legal arguments, but from the negative image of largely minority soldiers being commanding by mostly white officers. This is obviously very different but the brief would allow pro-ssm judges from seeming too partisan.

Daniel R. Pinello: Another way to consider whether the Republicans’ amicus brief might “affect legal considerations of the petitioners’ concerns” is to be mindful that about 50 friend-of-the-court briefs have been filed with the Supreme Court in the Perry and Windsor appeals in favor of marriage equality. Indeed, the scope and depth of amicus participation are remarkable. The organizations arguing in favor of same-sex marriage to the Court include the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, the American Anthropological Association, the American Psychological Association, the American Sociological Association, the Cato Institute, the National Education Association, the Organization of American Historians, 14 states, and numerous Fortune 500 companies (such as Morgan Stanley, Apple, AIG, Nike, Facebook, Intel, Verizon, and Google). Thus, in order for the GOP brief to be a singular influence in the resolution of these appeals, it would have to make uniquely compelling arguments to the Court. In light of the extensive and capable amicus involvement, I doubt seriously whether the Republicans can pull that one off.

Kathleen E. Hull: I assume “matrimonial lawyers” is a euphemism for divorce lawyers, in which case their filing of an amicus brief is amusing, if not surprising.

Now that you’ve heard from the experts, weigh in! Respond below or on Twitter using the hashtag #cambridgeideas.

Evan Gerstmann is associate professor of Political Science at Loyola Marymount University and the author of Same-Sex Marriage and the Constitution, 2nd edition.

Kathleen E. Hull is associate professor of Sociology at the University of Minnesota and the author of Same-Sex Marriage: The Cultural Politics of Love and Law.

Daniel R. Pinello is professor of Political Science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the author of America’s Struggle for Same-Sex Marriage and Gay Rights and American Law.

Shannon Gilreath is professor for the Interdisciplinary Study of Law at Wake Forest University School of Law and the author of The End of Straight Supremacy.

Michael J. Perry is professor of Law at Emory Law and the author of Constitutional Rights, Moral Controversy, and the Supreme Court and The Political Morality of Liberal Democracy.

Marsha Garrison is professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School and the co-editor of Marriage at the Crossroads: Law, Policy, and the Brave New World of Twenty-First-Century Families.

Latest Comments

Have your say!