Shopkeepers proudly display decorative beads and other jewelry, antique and modern lamps, and array of glass art-forms. Quaint cafés and restaurants line the quays, offering refreshment to curious browsers and residents alike. The island also houses an important museum documenting the centuries-old traditions of glass making, and one of the oldest churches in Venice, the seventh-century Santa Maria Donato.

Venetians did not invent glass making; rather they learned it from an assortment of ancient peoples whose artifacts were strewn along the Adriatic littoral and the Mediterranean Sea. Among the earliest of these peoples were the Egyptians, who were manufacturing glass as long ago as sixteen hundred BCE, but a large number of artifacts also come from the Romans during the first century CE. The first to invent blown glass were the Syrians; the technique diffused gradually throughout the Roman Empire from Alexandria to Great Britain. Veneto peoples not only adapted this technique but also obtained many of the raw materials for glass production from Syria and Alexandria. Their earliest furnaces date from the island of Torcello during the seventh-century. From the tenth century, contact with the Islamic world along the southeast axis of the Mediterranean also shaped the Venetian glass industry, which was situated in the district of Cannaregio until the end of the thirteenth century.

The presence of glass furnaces in medieval Venice, which was largely built of timber, presented a grave fire hazard. Therefore in 1291 for safety reasons the Great Council ordered the glassworkers to transfer their activities to the island of Murano, which was already a thriving metropolis with its own nobility and independent communal government. Glassworkers were afforded a host of privileges from Venice as an economic incentive to immigrate and produce, and from then on island manufacture thrived, furnishing both Europe and the Middle East with an assortment of mirrors, lamps, bottles, and decorative jewelry.

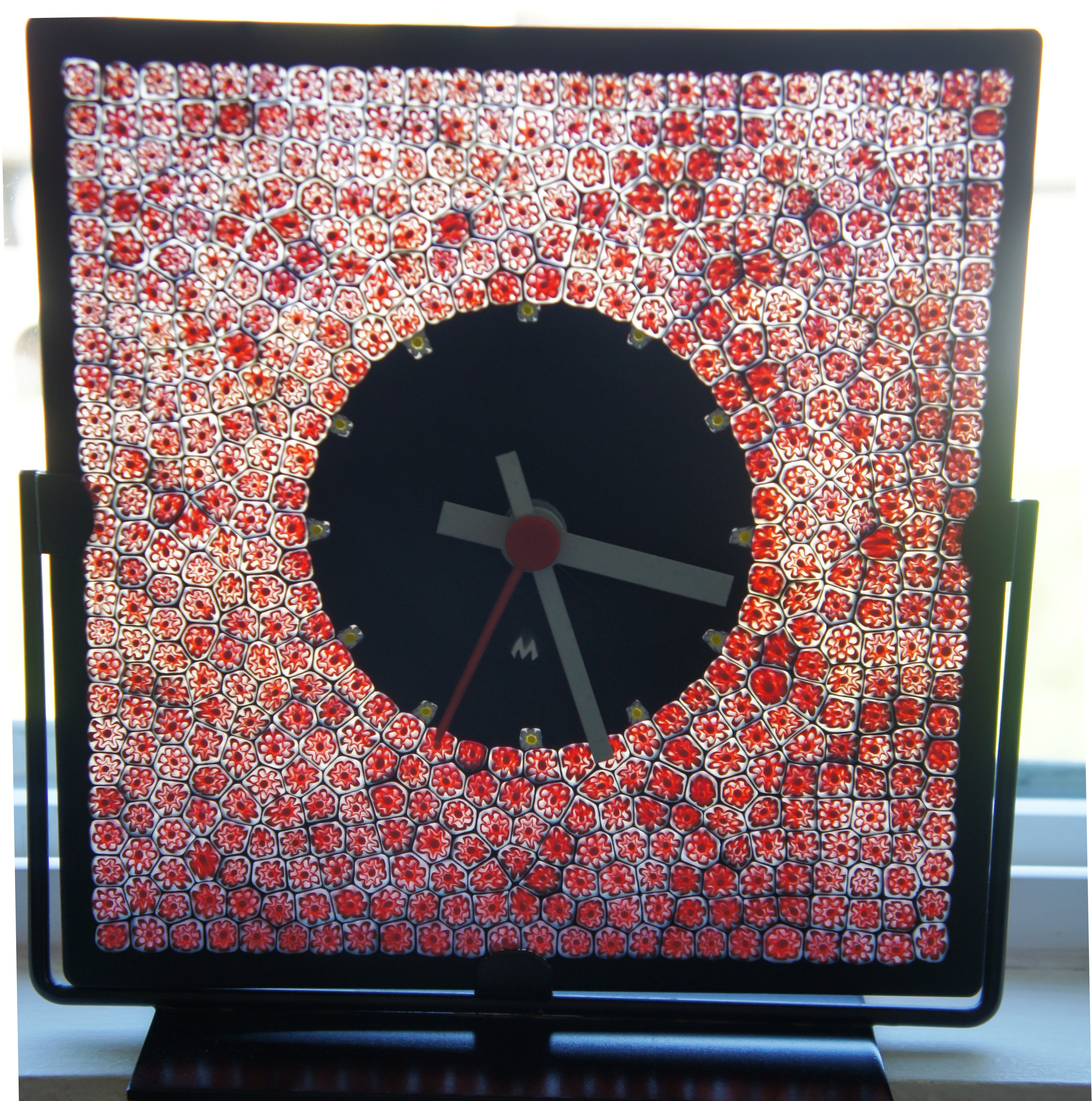

Among the most popular consumer items Murano produces today are the murrine, a mosaic of sliced glass canes fused together as pendants (Ercole Moretti, 1970), plates (Moretti, 1981), and bowls (Moretti, 1990s). Murrine are made from long, monochromatic or polychromatic glass rods, called canes, that are hand-pulled. The canes are then sliced, like carrots or cucumbers, and the “vegetable” pieces are then arranged in an asymmetrical design relative to the center of the pendant or plate, welded together, and enclosed in transparent glass. The effect is quite beautiful, resembling a colorful mosaic of Byzantine pavement, similar to the one in Murano’s precious Santa Maria e Donato. The canes themselves can be quite complex, either with geometric patterns or even with the face of an historical figure, like the Duke of Montefeltro (Moretti, 2000) or Botticelli’s Venice (Moretti, 2000).

Among the most popular consumer items Murano produces today are the murrine, a mosaic of sliced glass canes fused together as pendants (Ercole Moretti, 1970), plates (Moretti, 1981), and bowls (Moretti, 1990s). Murrine are made from long, monochromatic or polychromatic glass rods, called canes, that are hand-pulled. The canes are then sliced, like carrots or cucumbers, and the “vegetable” pieces are then arranged in an asymmetrical design relative to the center of the pendant or plate, welded together, and enclosed in transparent glass. The effect is quite beautiful, resembling a colorful mosaic of Byzantine pavement, similar to the one in Murano’s precious Santa Maria e Donato. The canes themselves can be quite complex, either with geometric patterns or even with the face of an historical figure, like the Duke of Montefeltro (Moretti, 2000) or Botticelli’s Venice (Moretti, 2000).

The founders of murrina-making on Murano are the Moretti family, descendants of Ercole Moretti (Co. Est. 1911), but many talented family dynasties over the last century deserve recognition for their glass production, including the Dalla Venezia, the Barovier, the Seguso, the Ferro, the Nason, and others. Still, the Moretti murrine, which you may observe in my photos, are among my favorites, and over the years I have purchased a number of their objects d’art, including plates, bowls, clocks, pendants, and beaded necklaces inspired by the Phoenicians, Africans, and Mayans. Every year the Moretti Company, as well as many other artisans on Murano, come out with new designs, and I am amazed at their steady production and creativity. While it is generally men who work the glass furnaces, historically women have produced the glass beads and murrina compositions. Glass-making is often a family affair that engages a network of kin in addition to other employees.

It is also interesting to note that historically, Murano’s glass masters jealously guarded their formulas from each other, from their workers who might potentially start activities of their own or sell secrets to outsiders, and even from their heirs. Great measures were taken to prevent “industrial spying” and to covet artistic innovation. Today one can find masters living and working in Murano that are not natives to the island, but this is only a recent phenomenon, for outsiders were generally kept out. What is more, it is easy to find glass shops in Venice that label merchandise from China “Murano Glass.” But the discerning eye can tell the difference between the industrial fakes and the hand made Murano works of art.

It is also interesting to note that historically, Murano’s glass masters jealously guarded their formulas from each other, from their workers who might potentially start activities of their own or sell secrets to outsiders, and even from their heirs. Great measures were taken to prevent “industrial spying” and to covet artistic innovation. Today one can find masters living and working in Murano that are not natives to the island, but this is only a recent phenomenon, for outsiders were generally kept out. What is more, it is easy to find glass shops in Venice that label merchandise from China “Murano Glass.” But the discerning eye can tell the difference between the industrial fakes and the hand made Murano works of art.

Latest Comments

Have your say!