Anthropologist Pita Kelekna’s years of research demonstrates countless ways in which horses influenced the tide of human civilization. Her book, The Horse in Human History tells this story, and she’ll be blogging about it in the coming weeks. First: some background.

When, where, and how was the horse domesticated?

Wild equids of diverse genera roamed the earth for 60 million years before the emergence of horse domestication, approximately 6000 years ago. Since remote times, though, the horse had been hunted by man for food. Thus, just as sheep, goats, and cattle slightly earlier, the horse was at first domesticated as a food source. Yet, in the course of its long evolution, the horse had developed specific traits that made it the fastest distance-running animal on the planet!

Writing a half-century ago about horse domestication, in his article “Horses and Battle-axes” Grahame Clark (1941) saw fit to comment:

“The importance of the horse in human history is matched only by the difficulties inherent in its study; there is hardly an incident in the story which is not the subject of controversy, often of a violent nature.”

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of the twentieth century and consequent increased western access to the research of Russian archaeologists, scholars now have answers to many of the issues that plagued Clark; they have identified the locus of initial domestication and have traced the spread of horse technologies across the Old World.But, let the reader be warned, the exact manner in which the horse transitioned from being a food-animal to its transport role in driving and riding continues to be fraught by bitter international debate.

It appears human overhunting during the Paleolithic and Mesolithic had resulted in mass extinctions of horse populations throughout much of Eurasia. However, on the semi-arid grasslands of the Eurasian steppes, wild horses managed to survive in large numbers into post-glacial times. While, today, there is general consensus that Equus caballus was domesticated on the Pontic-Caspian steppes by Indo-European speakers c 4000 BC(approximately the same time its equid cousin the donkey was domesticated by Nubian herdsmen in East Africa), there is little or no agreement as to when horseback riding first occurred.One school of thought opines that, in order to control a herd of horses, riding was necessary from the very start; additionally the mounted horse was early deployed in hunting wild horses and other prey.Critics of this hypothesis contend that there exists no unambiguous pictorial representation of a horse rider before 2000 BC.They consider the wild horse an intelligent and highly excitable animal that required centuries of breeding before it could be utilized as a steed.Still others recognize that, despite the inherent danger, agro-pastoralists likely practiced rudimentary riding in key activities such as seasonal herding and exploration for valuable metals and that the horse would have served in both pack and draft.

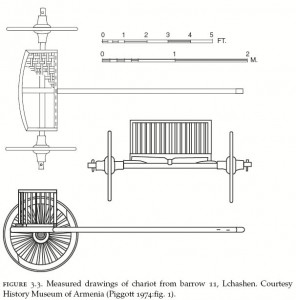

With regard to draft, the wheel was invented c 3400 BC and quickly spread across western and southern Eurasia.Carts and wagons, initially with bovid draft, were invaluable assets in farming but also allowed the farmer-herder-metallurgists of the Pontic-Caspian to migrate with the horse westward into Europe and eastward across the Asian steppes.In the east, the Yamnaya cultural group quickly penetrated the steppe interior and within a millennium had reached the Ural river.Further east, on the Ural-Tobol steppe, another momentous invention took place c 2100 BC.Pole-and-yoke draft, originally designed for paired bovids, was ill-suited to equine anatomy.As a consequence, concerted efforts in construction – wickerwork sides and spoke-wheels – had been undertaken to lighten the bulky cart.Weighing less than 34 kg, one twentieth the weight of ancient wagons, the horse-drawn chariot (see right) was a new breed of vehicle, infinitely lighter and swifter than the older solid-wheeled conveyances.Equipped with this agile war chariot, tribes from the steppes successfully invaded the sedentary centers of civilization:the Hittites, Anatolia in the west; the Indo-Aryans, the Indus Valley in the south.

farming but also allowed the farmer-herder-metallurgists of the Pontic-Caspian to migrate with the horse westward into Europe and eastward across the Asian steppes.In the east, the Yamnaya cultural group quickly penetrated the steppe interior and within a millennium had reached the Ural river.Further east, on the Ural-Tobol steppe, another momentous invention took place c 2100 BC.Pole-and-yoke draft, originally designed for paired bovids, was ill-suited to equine anatomy.As a consequence, concerted efforts in construction – wickerwork sides and spoke-wheels – had been undertaken to lighten the bulky cart.Weighing less than 34 kg, one twentieth the weight of ancient wagons, the horse-drawn chariot (see right) was a new breed of vehicle, infinitely lighter and swifter than the older solid-wheeled conveyances.Equipped with this agile war chariot, tribes from the steppes successfully invaded the sedentary centers of civilization:the Hittites, Anatolia in the west; the Indo-Aryans, the Indus Valley in the south.

Earlier, agro-pastoralists, offshoots of Yamnaya culture, had advanced eastward as far as the Yenisei river.By 2000 BC, Indo-Europeans had reached the Tarim basin, and c 1180 BC the steppe war chariot was introduced to Shang China.At Muye 1045 BC, Zhou massed chariotry effectively overthrew the Shang dynasty to dominate northern China for several centuries, c 800 BC introducing iron technologies.But another breakthrough innovation had already taken place.Whereas during the second millennium BC scenes of hunters on horseback had been depicted on both western and eastern steppes, now competent military riding was finally realized, as Iranian-speakingnomads with the recurved composite bow – Scythians, Sarmatians, and Saka – engaged in cavalry combat across the Eurasian steppes.Western cavalry warfare culminated c 550 BC in the Achaemenid conquest of earlier nuclear states from the Indus to the Mediterranean. In the east by 221 BC, Qin Shi Huangdi’s intensive chariot and cavalry campaigns had consolidated the whole of China.

Next week: The Przewalski Wild Horse >>

Sources:

. 1941 Horses and Battle-axes. Antiquity 15 (57):50–70.

1992 Fossil Horses: Systematics, Paleobiology, and Evolution of the Family Equidae. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Piggott, Stuart. 1974 Chariots in the Caucasus and China. Antiquity 48:16–24.

Latest Comments

Have your say!