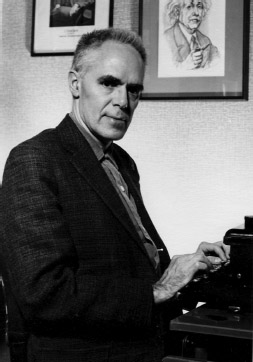

Continuing from last Thursday – Don Albers’ long interview with math puzzle legend Martin Gardner.

Yes, he once edited a magazine for girls.

Newcomers: start from the beginning here >>

Gardner: That’s right, it’s not until I started selling stories to Esquire that I thought I could make a decent living as a freelance writer, but Esquire changed editors after I had sold them many stories. The new editor had a different policy, and he didn’t care for the kind of stories I was writing. So I moved to New York City because that’s where all the action is for writers. And that’s when I got a job at Humpty Dumpty’s Magazine.

Gardner: That’s right, it’s not until I started selling stories to Esquire that I thought I could make a decent living as a freelance writer, but Esquire changed editors after I had sold them many stories. The new editor had a different policy, and he didn’t care for the kind of stories I was writing. So I moved to New York City because that’s where all the action is for writers. And that’s when I got a job at Humpty Dumpty’s Magazine.

DA: Now that’s a curious move.

Gardner: I had a friend who worked for Parents’ Institute, and who was in charge of their periodicals for children. They were starting a new magazine called Humpty Dumpty’s, and were looking for activity features, where you fold the page or stick something through the page, or cut; where you destroy the page. So he hired me to do the activity features for Humpty Dumpty’s.

DA: Had you ever done anything like that?

Gardner: No, but I grew up on a magazine called John Martin’s Book. Everybody’s forgotten about it. It flourished in the twenties, and the art editor, George Carlson, did activity features for John Martin, where you cut things out of the page and fold them intothings, pictures that turned upside down, or you held them up to the light and saw through. I’d always been intrigued by George Carlson’s activity features, and so I started out just sort of imitating George Carlson, taking up where he left off, and inventing new ideas of my own. I did that for eight years. I did the activity features, and I did a short story in every issue about the adventures of Humpty Dumpty, Jr. The magazine is supposed to be edited by Humpty Dumpty, who’s an egg. The wife of the publisher thought of the idea of having Humpty edit the new magazine. She suggested a series of tales about a little egg, who was Humpty Dumpty’s son. I started with the first issue of the magazine, and continued as a “contributing editor” for eight years. The magazine came out ten times a year, so I had eighty short stories about Humpty Dumpty, Jr. that I’ve never had reprinted. I haven’t found a publisher for them yet. Most of the books that come out for children now are done by artists, and they’re mainly art books with small amounts of text underneath the pictures. Not being an artist may be one reason I can’t sell any of these stories. I worked hard on these stories. I have the rights to the stories but not to their illustrations.

I also did a poem in every issue —“Advice from Humpty Sr. to His Son.” —Poems of moral advice. They’re just jingles, and I did get a book out of them. It was published by Simon and Schuster, titled Never Make Fun of a Turtle, My Son. The title refers to a poem about how you shouldn’t make fun of people who are different from you.

DA: This must have taken a lot of time to do.

Gardner: Yes, it was my only job. I’d gotten married and we had a son to support, and I couldn’t make a living in New York freelancing. I made maybe a sale or two of something trivial, but not enough to live on. So I jumped at the chance to work for Parents. I worked at home. There was a short period where I went to the office and edited a magazine for girls called Polly Pigtails. I was Polly Pigtails. I wrote a letter for each issue from Polly Pigtails to her readers. It later changed its name to Calling All Girls.

DA: So you actually edited a magazine aimed at girls.

Gardner: Yes, I did that, for maybe the first six issues. And I also started another magazine that lasted only three issues, called Piggity, and for that I did a short story in each issue about a little pig. I also had some good ideas on activity features. Are you familiar with the “Klutz” books?

DA: Yes.

Gardner: Well the fellow who puts those out, John Cassidy, is a friend. He’s been out to see me a few times, and I’ve given him material for several of his books. He was out to see me just last month, looking for activity features for a book he is going to bring out. So I photocopied about 50 activities features for Cassidy. And he bought them all. I don’t know how he’s going to use them. I don’t know how he’s going to redo the art. So I did get some extra mileage out of those issues. I had some novel ideas. For example, one feature was called “See Tony Eat Spaghetti.” You’d punch a hole in Tony’s mouth, and there was a plate there. You take a white piece of string, and push it from the back of the page through his mouth, and then you pull the string out of the mouth and you go “ssslurp.” You pull it from the back, so you see Tony slurp up spaghetti. Shari Lewis’ father was a magician. I knew him, and I knew Shari slightly when she lived in New York. She copied Tony’s picture on a big piece of cardboard and demonstrated it on her television show. She

was a fine ventriloquist, one of the best, using a hand puppet called Lamb Chop.

DA: She was very popular for a long time.

Gardner: She was a wonderful ventriloquist. Her father performed magic, under the name of Peter Pan. Occasionally Shari would do a little magic trick on her show. She died last year.

DA: She was young when she died.

Gardner: Yes, she was quite young. She was married to Mr. Tarcher of Tarcher Books.d

DA: Your work with children’s magazines continued to about 1956. By 1957 you were at Scientific American. So there was not much of a hiatus between Humpty Dumpty’s and Scientific American.

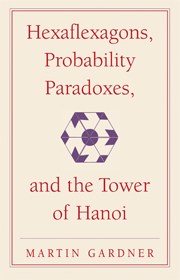

Gardner: No, I stopped working for Humpty Dumpty’s to start the column, “Mathematical Games,” at Scientific American. I couldn’t do both. It started with a sale in December 1956, of an article on Hexaflexagons. That was not a column, but it led to the column. When Gerry Piel, the publisher of Scientific American, called me and suggested the column, that was when I resigned from Parents.

DA: How long did it take you to accept Piel’s offer? Gardner: I accepted it instantly, with surprise and delight. Indeed, my first column appeared in the January 1957 issue.

DA: You must have had a lot of confidence to take on a monthly column on mathematics in a sophisticated magazine like Scientific American, especially in view of the fact that the last math course you had was in high school.

Gardner: I had always been interested in recreational math ever since as a boy my father gave me a copy of Sam Loyd’s famous Cyclopedia of Puzzles. In later years I would edit for Dover two paperbacks of Loyd’s mathematical puzzles. After Piel proposed that I do a monthly column I rushed to the used bookstores area of Manhattan to buy all the books I could find on recreational math. That was when I obtained my first copy of W. Rouse Ball’s classic Mathematical Recreations and Essays. It was a great source of ideas for my early columns.

DA: A lot of people are astonished that anyone could turn out a column on mathematical games every single month for twenty-five years.

Gardner: Perhaps they don’t realize I had no other job. I’m not a professional mathematician who has to teach a course in mathematics, and then write. To me, it’s hard to imagine how a professional mathematician would have time to even write a book. I had nothing else to do, except research for those columns, and write them up.

DA: Well, having the time certainly helps. Most people that I’ve ever talked to about your Scientific American columns know that that was your job, but they’re still awed by the fact that you turned out something really

sparkling every month. It’s one thing to write something every month, but that doesn’t mean that it’s going to be inspirational or great fun to read each time.

Gardner: I miss doing those columns, they were a lot of fun, and I met many fascinating people while doing them. Once the column got started I began hearing from people like Sol Golomb and John Conway, who were really doing creative work that had a recreational flavor. That kept the column going. It became much more interesting after I began getting feedback from people like John Conway, Ron Graham, Don Knuth, and many others.

DA: What is it about mathematics that you find so attractive?

Gardner: I suppose it’s the fact that in mathematics, unlike in science which is fallible, you can prove astonishing results with absolute certainty. Of course a proof must always be within a formal system. The Pythagorean theorem, for example, is certain only within the formal system of Euclidean geometry. It doesn’t become false when it fails in non-Euclidean geometries because such geometries are different formal systems. Mathematical theorems are timeless truths, analytic in nature like the great truth that three feet are in a yard.

DA: Complete the following: “ I enjoy mathematics so much…”

Gardner: Because it has a strange kind of unearthly beauty. There is a strong feeling of pleasure, hard to describe, in thinking through an elegant proof, and even greater pleasure in discovering a proof not previously known. On a low level I have experienced such a pleasure four times. (1) I discovered the minimal number of acute triangles into which a square can be dissected. (Coxeter includes the dissection in his classic Introduction to Geometry.) (2) I found a minimal network of Steiner trees that join all the corners of a

chessboard. (3) I constructed a bicolor proof that every serial isogon of 90 degrees—a polygon with all right angles, and sides in 1,2,3… sequence—must have a number of sides that is a multiple of 8. (4) I devised a novel way to diagram the prepositional calculus. Life, Consciousness, and Mysterians Probably my most famous column was the one in which I introduced Conway’s game of Life. Conway had no idea when he showed it to me that it was going to take off the way it did. He came out on a visit, and he asked me if I had a Go board. I did have one, and we played Life on the Go board. He had about 50 other things to talk about besides that. I thought that Life was wonderful—a fascinating computer game. When I did the first column on Life, it really took off. There was even an article in Time magazine about it.

DA: Wasn’t there a Life journal of sorts for a while?

Gardner: Yes, Bob Wainright did a periodical called Lifeline. Lots of famous mathematicians contributed to it.

DA: I don’t think there is any doubt that when students encounter Life today for the first time, there’s still a lot of excitement. It has a natural quality to it that captures people.

Gardner: And there are people still working on Life, still making new discoveries?

DA: There’s a guy up at MIT named Hans Moravec who’s done some work on Life.

Gardner: He’s the robot man. In one of his books he explained a fast algorithm for Life. He’s in charge of a robot laboratory at Carnegie-Mellon University. He is of the opinion, and he’s done two books about it, that’s it’s only a matter of about 40 years from now until computers will be doing everything that humans do. They will be self-aware, they’ll have free will; they’ll be writing great poetry. We’ll be the ancestors of a new breed of beings that are going to be the computers. Moravec actually believes it. His first book about this was called Mind Children. These are the children that we are going to spawn, this race of super computers. The human race will become obsolete. The computers are going to take over, and then they’re going to start exploring space, and colonizing the galaxy. He really believes it.

You know the problem of consciousness is a hot topic right now. There have been half a dozen books published just in the last year or two. All of them are trying to figure out what it is in the brain that makes you self-aware. Of course, materialists like Moravec, and Churchland and his wife, are of the opinion that is it only going to be a short time until we figure out how the brain makes itself aware. But there is another school of philosophy that is coming into prominence now, with which I am sympathetic. They’re called the Mysterians. The Mysterians, and this includes a number of very top notch philosophers like Donald Chalmers, Colin McGinn, John Searle, Thomas Nagel, Jerry Fodor, Noam Chomsky, and a bunch of others, are of the opinion, and I share this view, that consciousness is something so mysterious that no one has the slightest idea how the brain makes itself aware, and we may never find out. That’s the extreme Mysterian position, that we don’t have the intellectual capacity ever to solve the problem of consciousness. It may be something beyond our power to understand; the way calculus is beyond the mind of a chimpanzee. It’s an interesting point of view because it may be that there are some questions beyond the reach of science because of the limitations of our present brain. Perhaps in a million years from now, if we evolve with bigger brains, we’ll solve it. Roger Penrose is a Mysterian. This was one of the themes of his famous book The Emperor’s New Mind, for which I wrote the introduction. We Mysterians think consciousness won’t be understood for at least a long, long time. Also, the Mysterians believe that self-awareness and free will are two names for the same thing. If you try to imagine yourself without self-awareness, then you can’t imagine yourself having free will to make decisions. You’d be like an automaton. “I just write as clearly as I can.”

You know the problem of consciousness is a hot topic right now. There have been half a dozen books published just in the last year or two. All of them are trying to figure out what it is in the brain that makes you self-aware. Of course, materialists like Moravec, and Churchland and his wife, are of the opinion that is it only going to be a short time until we figure out how the brain makes itself aware. But there is another school of philosophy that is coming into prominence now, with which I am sympathetic. They’re called the Mysterians. The Mysterians, and this includes a number of very top notch philosophers like Donald Chalmers, Colin McGinn, John Searle, Thomas Nagel, Jerry Fodor, Noam Chomsky, and a bunch of others, are of the opinion, and I share this view, that consciousness is something so mysterious that no one has the slightest idea how the brain makes itself aware, and we may never find out. That’s the extreme Mysterian position, that we don’t have the intellectual capacity ever to solve the problem of consciousness. It may be something beyond our power to understand; the way calculus is beyond the mind of a chimpanzee. It’s an interesting point of view because it may be that there are some questions beyond the reach of science because of the limitations of our present brain. Perhaps in a million years from now, if we evolve with bigger brains, we’ll solve it. Roger Penrose is a Mysterian. This was one of the themes of his famous book The Emperor’s New Mind, for which I wrote the introduction. We Mysterians think consciousness won’t be understood for at least a long, long time. Also, the Mysterians believe that self-awareness and free will are two names for the same thing. If you try to imagine yourself without self-awareness, then you can’t imagine yourself having free will to make decisions. You’d be like an automaton. “I just write as clearly as I can.”

DA: Can you tell me a little bit more about how you actually approach writing? You previously said something about how you did your monthly columns over a long period of time. You write about many other things as well. Do you have a different style or a different mode when you write about pseudoscience?

DA: Can you tell me a little bit more about how you actually approach writing? You previously said something about how you did your monthly columns over a long period of time. You write about many other things as well. Do you have a different style or a different mode when you write about pseudoscience?

Gardner: I don’t think so. I’ve never worried about style. I just write as clearly as I can, and I suppose it’s improved over the years. I get interested in a topic, and I do as much research as I can on it. I have my library of working tools, so I can do a lot of research right here at home. I usually rough out the topic first, just list all the things that I have to say, and then I sit down and try to put it together on the typewriter. It’s all kind of a sequence. That is hard to explain. It comes easy for me, I enjoy writing and I don’t suffer from writer’s block, where I sit and wonder for an hour how I’m going to phrase the opening sentence.

DA: So you’re not like some of these people who say ‘OK,’ I’m going to get up early each day and write or I’m going to write each day over a fixed period.

Gardner: No, I don’t have any rigorous schedule.

DA: I’m glad to hear that. That’s probably another reason why you’re going to live 150 years.

Gardner: Well, I doubt that, but I don’t have any fixed schedule. My wife Charlotte and I could take off in the middle of the week and go somewhere for a few days and come back. I can work all day Sunday.

Latest Comments

Have your say!